https://www.sgr.fi/sust/sust266/sust266_aikio.pdf

" A Linguistic Map of Prehistoric Northern Europe.

Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia = Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 266.

Helsinki 2012. 63–117.

Luobbal Sámmol Sámmol Ánte (Ante Aikio)

Giellagas Institute

University of Oulu

An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory *

“Sámiid boahtimušas ii leat gullon, ahte livččo boahtán gosge.” – Johan Turi

This essay deals with the study of the ethnolinguistic past of the Saami. In recent years many novel findings have emerged in the field of Saami historical linguistics, and the interpretation of these new results allows a coherent timeline of the development of the Saami languages to be established. The Proto-Saami language appears to have first evolved somewhere in the Lakeland of southern Finland and Karelia in the Early Iron Age. A broad body of evidence points to the conclusion that the Middle Iron Age (ca. 300–800 AD) in Lapland has been a period of radical ethnic, social, and linguistic change: in this period the Proto-Saami language spread to the area from the south and Saami ethnicities formed.

Prior to this, Lapland was inhabited by people of unknown ethnicity that spoke non-Uralic languages, many relics of which survive in Saami vocabulary and place-names. In the archaeological record of Lapland the Middle Iron Age is an obscure period characterized by sparse finds and lack of ceramics and iron production. This apparent correlation between ‘archaeological invisibility’ and major ethnolinguistic change poses intriguing questions regarding the nature of this period of Saami prehistory.

1. Introduction

Since the very beginning of scientific study of the history of the Saami, scholars have wonde-red about our “origin” – whence we came and why we speak Finno-Ugric languages related to Finnish and Hungarian. Initially the question of our origins was approached from two very different angles. On the one hand, comparative linguists turned to seek these origins from be-yond the Volga or the Urals, as the linguistic relationship of Saami languages to Finno-Ugric was solidly demonstrated in the 18th century already. On the other hand,cultural and physical anthropologists started early on to emphasize the difference of our ethos and race from those of neighboring peoples, including the linguistically related Finns.

A Linguistic Map of Prehistoric Northern Europe.Suomalais-Ugrilaisen Seuran Toimituksia = Mémoires de la Société Finno-Ougrienne 266. Helsinki 2012. 63–117.

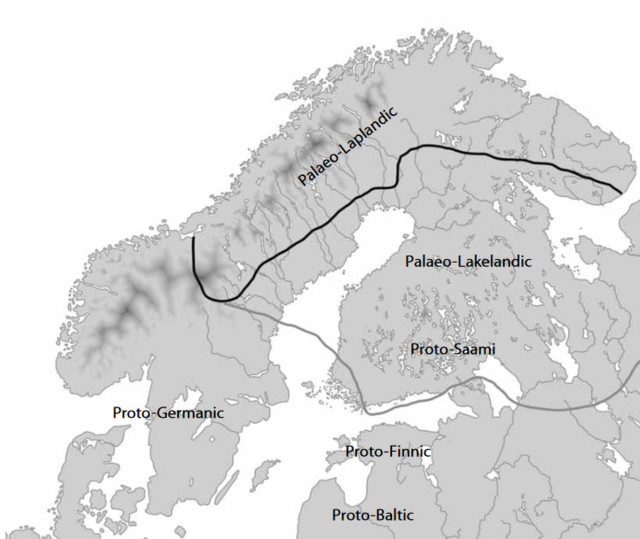

Figure 1. The linguistic situation in Lapland and the northern Baltic Sea Area in the Early Iron Age prior to the expansion of Saami languages; the locations of the language groups are schematic. The black line indicates the distribution of Saami languages in the 19th century, and the gray line their approximate maximal distribution before the expansion of Finnic.

RJK: Hölynpölyä. Muka "rautakauden alussa (Suomessa 500 e.a.a.) "Baltiassa olisi puhuttu kantabalttia ja kantasuomea"! JO NOIN 3000 e.a.a. SUOMEEN TULLUT ITÄBALTTILAINEN VASARAKIRVESKIELI (joka oli myös "sotavaunukieli") OLI EHTINYT KAUEMMAKSI KANTABALTISTA KUIN NYKYLIETTUA! JA SU-KIELI OLI TULLUT SUOMEEN ENNEN SITÄ!!! Suomen länsirannikolle oli tullut myös LÄNSIBALTTILAINEN KIELI VÄHÄN ENNEN SITÄ!!!

As such speculations combined with social Darwinist ideologies, it emerged as a mystery to be pondered by many scholars how we could be linguistically related to sedentary Finno-Ug-ric peoples that had evolved to a higher cultural level, even though our racial characteristics suggested a very different history – or perhaps a lack of history altogether.

The naïveté of such thoughts is now easy to point out. What is less easy to see,though, is how the legacy of old paradigms now manifests itself in new forms in today’s theories. The clash between linguistic and anthropological findings of Saami origins has not disappeared, even though methods of population genetics have been substituted for craniometric measurements. While linguists trace Saami origins via the Finno-Ugric connection far to the Russian taiga, archaeologists find evidence of cultural continuity in Lapland since the pioneers who follo-wed the receding ice sheet,and geneticists describe the Saami population as an ‘outlier’ in the European context. A synthetic view of Saami ethnogenesis seems perhaps farther from our reach than ever, as there is hardly a single question in the field of Saami prehistory on which broad agreement betweenscholars in the various disciplines could be found.

65 An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory

Perhaps nowhere can this be seen better than in the fact that there is no unanimity of what the term ‘Saami’ even means when applied in a prehistoric context. This essay is an attempt to present a synthetic view in a fragmented field of study by piecing together a picture of what we currently do know and what we still do not know of the origin of Saami ethnicities.

Comparative linguistics provides effective methods for tracing the origins of languages, and due to the ethnolinguistic connection linguists have often dominated discussions on ethnic prehistory. Indeed, it cannot be denied that language is an important component of ethnic identity – it is, in fact, a component so central that ethnic boundaries largely coincide with linguistic ones. There are, of course, also many exceptions to this basic correlation, such as cases where two groups of people do not share a common ethnic identity in spite of speaking essentially the same language (as in the case of the Serbs and the Croats in modern Europe, for example). However, such cases are recognized as exceptional precisely because they go against the seemingly common rule that speakers of one language tend to consider them-selves as members of one group, and those that speak another members of a different group.

The fact that a pervasive connection between language and ethnicity can be synchronically observed in the real world has given rise to an idea that this connection is also diachronically straightforward. It seems to be an unstated premise that lurks on the background of many lin-guists’ thinking that the origin of a language also coincides with the ethnogenesis of its spea-kers. This has also been the case with my own writings on the topic, such as Aikio (2006), where the ethnically loaded term ‘Saami homeland’ is used in a purely linguistic sense, in re-ference to ‘the original speaking area of Proto-Saami’. This way of thinking must be rejected as misleading, however.

It is, in fact, quite easy to see that ethnogenesis is not a direct result of the formation of new languages through the breaking up of a proto-language. For example, an ethnic category such as ‘Swedes’ has not emerged through the separation of a ‘Swedish’ language from Proto-Scandinavian. On the contrary, the mere idea of such a distinct ‘language’ has served as a background upon which the idea of an ethnic group could be created. But language does not need to determine the boundaries of an ethnic group even if it determines its prototype. By the linguistic criteria of shared innovations or mutual intelligibility one cannot find anything that would delimit all dialects of ‘Swedish’ as a coherent whole distinct from ‘Norwegian’ and ‘Danish’. On the other hand, there are Scandinavian language varieties spoken within Sweden such as Övdalian,which by the criterion of lack of mutual intelligibility as well as by their speakers’ own opinion are clearly distinct languages (although refused to be officially recognized as such by the state of Sweden). Still, speakers of Övdalian consider them selves ‘Swedes’ and not a distinct ethnic group (Melerska 2010). Moreover, even groups speaking linguistically unrelated languages, such as Meänkieli or Torne Valley Finnish in northern Sweden, have become secondarily incorporated to the ethnic category of ‘Swedes’.

66 Ante Aikio

Hence, even if ‘ethnic identity’ is a category intimately tied to the concept of ‘native language’, ethnogenesis often cannot be explained as a direct result of glottogenesis – in part because there are many answers to how one should define ‘native language’ on an individual level (Skutnabb-Kangas 2000: 105–115) and to what counts as a ‘language’ on a group le-vel. On the other hand, one should not go as far as to reject linguistic explanations of ethno-genesis altogether. While linguists have often oversimplified the connections of language and ethnicity, in other subfields of the humanities the situation is more the opposite – in cultural studies ethnicity has remained a highly controversial topic subject to much critical discussion and overproblematization, and the role of native language as a criterion of ethnic identity has often been overlooked in this discourse.

A popular view expressed by Barth (1969), for instance, is that ethnicity is a construct crea-ted or chosen to uphold a group’s difference from its neighbors. In the context of Saami pre-history Barth’s views have led scholars such as Odner (1983) and Hansen and Olsen (2004) to see the Saami ethnogenesis as a process of gradual unification, which could be explained as a reaction to the political, economic, and cultural pressure caused by intensified interaction with Scandinavians in the Iron Age. While there is certainly a grain of truth to such a scena-rio, the theory still reminds one of a three-legged stool missing a leg. As languages are born through a process of linguistic diversification, no completely new language could ever have been ‘created’ as an ethnic marker in response to outside pressure.Even if the envisioned pro- cess of ethnic unification has taken place in Lapland – and it well may have – we still need a wholly different explanation to how the Proto-Saami language became adopted as a key component of the emergent ‘Saami’ identities.

The intimate connection between language and ethnicity implies several things for the inter-pretation of Saami prehistory. It is worth bearing in mind that the term ‘Saami’ can be reaso-nably applied only to societies thought to have used some form of Saami as their main me-dium of in-group communication. Because of this, it is sensible to speak of ‘Saami people’ and ‘Saami culture’ only in connection with periods when Saami languages have existed, but not before that. Even so, it must also be borne in mind that ‘Saami’ in this sense is merely a linguistic umbrella term, and we must seriously consider the possibility that in prehistoric times Saami languages have been spoken in communities that differed radically from the historical Saami in terms of their culture, livelihoods, or ethnic identity.

While all this might seem easy to fathom, in practice one gets to learn that it is not. For in-stance, it is not at all uncommon to see Stone Age dwelling sites or rock art in Lapland cha-racterized as “Saami” in scholarly references and popular texts alike. Even so, those acquain-ted with very basic facts of the historical development of languages are aware that the Saami languages - or indeed,any languages spoken today - cannot possibly have existed in the Stone Age. Consequently, there can have been no ‘Saami’ in the Stone Age either; people who did not speak Saami and did not call themselves Saami should not be called Saami by us either. It is another thing that the Saami, like all peoples, have their Stone Age linguistic, cultural, and genetic ancestors.

67 An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory

Thus, the right question to ask is how Saami ethnicities later emerged through the interplay of diverse linguistic, cultural, and genetic components. In the present state of research the details of this process are largely unknown.

While our current knowledge will hardly translate into an exact theory of Saami ethnogene-sis, it is a task in itself to try to create a synthesis of what we know and to formulate the questions we should ask ourselves next. The last decade has produced many new results and interpretations in the field of Saami historical linguistics, and a rather uniform view of the chronology and areal contacts of the proto-stages of Saami languages has emerged among linguists (Aikio 2006; Kallio 2009; Häkkinen 2010a, 2010b; Saarikivi 2011; Heikkilä 2011). These new linguistic views are of interest to scholars in all fields of Saami prehistory, as they allow us to place sociolinguistic events of the past in space and time, and thus to partially reconstruct the sequence of major ‘speech community events’ (in the sense of Ross 1997) which led from the Uralic protolanguage to the emergence of Saami languages in Lapland.

RJK: Nuo "tulokset" ovat virheellisiä: niillä "siirretään" kantaurali kokonaista 5000 vuotta liian myöhäiseen ajankohtaan (jotta "Pohjolaan saadaan "tilaa" Adolf Hitlerin "kanta-arjalaisille kanatakermaaneille").

Somewhere along this timeline of linguistic development Saami ethnicities have taken shape in the groups speaking these languages. The setting up of a linguistic chronology for Saami will thus also allow us to determine the boundaries between possible and impossible theories of Saami ethnogenesis. It would seem a reasonable requirement for such a theory that it must address the question why the Saami people speak Saami languages,as even the name ‘Saami’ as a label for an ethnic category is tied to the very existence of the languages themselves.

I shall discuss below results achieved on various questions in Saami historical linguistics, fo-cusing largely on loanword strata of varying age, which bear witness to the prehistoric inter-actions of groups speaking different languages. An attempt for a synthesis of these results will prompt us with new and surprising questions about past ethnicities in Lapland.

2. The position of Saami in the Uralic language family

The Saami languages, occupying the extreme northwestern parts of continental Europe, are a geographically peripheral branch in the Uralic family of languages.Whatever theory of Uralic Urheimat one might choose to endorse, it is quite obvious that the original speaking area of the Uralic proto-language must have been located far from Lapland, and certainly such an outlying area must have become Uralicized only in the last phase of the sequence of linguis-tic expansions that have formed the language family in the first place. It is, at any rate, clear that the first people to colonize Lapland after the last Ice Age were not speakers of Uralic languages, as the whole language family is hardly much older than approximately 4000 years (an up-to-date discussion on the dating of Proto-Uralic is provided by Kallio 2006).

Saami has a special relationship with Finnic, the only branch of the family known to have been in contact with Saami.In the traditional framework of Uralic taxonomy this special rela- tionship has been understood in a genetic sense:Saami and Finnic languages would constitute a ‘Finno-Saamic’ subgroup in the family,and thus derive from an intermediate Finno-Saamic proto-language (which in older research has been misleadingly called ‘Early Proto-Finnic’).

68 Ante Aikio

Even so, it has always been clear that the main bulk of features shared by Saami and Finnic are due to language contact rather than genetic inheritance. This is certainly true of many morphosyntactic isomorphisms, and also loanwords have been adopted from Finnic to Saami in huge numbers. Some scholars, notably T. Itkonen (1997), have pursued the idea that all the features common to Finnic and Saami and separating them from the rest of the Uralic family could be explained in this way. Itkonen’s conclusions have been criticized by Sammallahti (1999: 72–74), who points out that there is more vocabulary common to Finnic and Saami than Itkonen acknowledges, and also draws attention to specifically Finno-Saamic cognate grammatical endings such as the mood markers *-ŋśi- and *-kśi- and the infinitive ending *-tak.

How one should evaluate the arguments for and against a Finno-Saamic genetic subgrouping depends on what kinds of probative power one assigns to the various levels of language in taxonomical questions. As regards shared vocabulary items, it is difficult to see the evidence for Proto-Finno-Saamic as compelling; in methodological discussions it has been pointed out that shared vocabulary as such is a weak criterion for subgrouping, as lexical innovations can easily spread between dialects and languages already separated (e.g., Fox 1995: 220). In the case of Saami and Finnic the use of lexical evidence is further complicated by the existence of ‘etymological nativization’, a process whereby speakers bilingual in two related languages identify patterns of regular sound correspondence and then apply these productively by nati-vizing loanwords in shapes that accord with the sound correspondences attested in cognate vocabulary. Such processes have been very productive in the loanwords transferred between Finnic and Saami, and they have often made even recent borrowings deceptively look like cognate items from a phonological point of view (Aikio 2007a).

Keeping this in mind, one must treat with some doubt claims such as that Saami and Finnic may share as many as 220 cognate words not attested elsewhere in the Uralic family (Sam-mallahti 1999:74),as many or even most of such word-roots may simply be undetected borro-wings between the already differentiated language branches. On the other hand, T. Itkonen’s (1997) attempt to undermine the validity of the ‘Finno-Saamic’ subgrouping on the basis of calculations of the numbers of lexical cognates must be treated with the same doubt, as he, too, seems to overestimate the probative force of lexical correspondences in genetic subgrouping.

In the domain of morphology a few specifically Finno-Saamic cognate morphemes are well established. It is problematic, though, that their further origin remains unknown and none of them can be unambiguously shown to have arisen as a result of some specific innovation; it is possible that they were simply inherited from an earlier proto-language stage and their cog-nates in more eastern Uralic languages either were lost or remain unidentified. Phonology is the domain where more precise methods for detecting innovations could be applied, but inte-restingly, it has proved very difficult to find decisive evidence of sound changes common to Saami and Finnic.

69 An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory

The most plausible candidate for such a change is the development of a labial vowel in un-stressed syllables via a change *Vw > *oj (Sammallahti 1999: 72–73). But as recently shown by Kuokkala (2012),closer inspection reveals the correspondences between Saami and Finnic unstressed labial vowels as highly diverse, which suggests more complicated paths of deve-lopment. As proposed by E. Itkonen (1954) already, the Proto-Uralic sequences *-aw- and *-iw- seem to have developed differently in Finnic (as in Fi kanto ‘tree stump’< Proto-Uralic *kïntaw vs. Fi käly < Proto-Uralic *käliw), whereas Saami shows no such distinction. If the unstressed labial vowels really are a common innovation instead of a parallel development, then two such vowels (*o and *u/*ü) need to be reconstructed in Proto-Finno-Saamic, which later merged in Saami (see also Kallio, forthcoming). Another problem is that Saami shows a distinction between an unstressed labial vowel (Proto-Saami *-ō ~ *-u-) and an unstressed sequence of a labial vowel followed by a palatal glide (Proto-Saami *-ōj ~ *-ujë-), both of which have the same correspondents in Finnic. How this is to be accounted for in terms of phonological reconstruction is not clear; the history of unstressed labial vowels requires further study.

The question whether Finno-Saamic is a valid genetic subgroup remains so far unsolved, and perhaps insoluble. The taxonomic issue is further complicated by the fact that also other Ura-lic languages have been spoken in the immediate vicinity of Finnic and Saami, but these be-came extinct during the expansion of East Slavic. Rahkonen (2011a) has convincingly argued on the basis of toponomastic studies that the Uralic language spoken by the ‘Chudes’ in areas surrounding the city of Novgorod was neither Finnic nor Saami. In the Early Middle Ages there still was an unbroken continuum of Uralic languages spoken by the historical Chude, Merya, Muroma and Meshchera tribes that linked Finnic and Saami to Mordvin. We know nearly nothing of the concrete features of these extinct languages, but there are speculative theories such as Rahkonen’s (2009) attempt to link the Meshchera language in the Oka River basin with Permic on the basis of certain resemblances in place-names.

Questions regarding the taxonomic position of Finnic and Saami are obviously very difficult to answer as long as we lack knowledge of the features of the extinct Uralic languages once spoken in their vicinity. Nevertheless, due to the very limited number of possible common Finno-Saamic innovations it seems clear that if such an intermediate proto-language really existed, it must have been merely a short transitory period before the separation of Pre-Proto-Finnic and Pre-Proto-Saami into distinct speech communities.On the whole,though, the taxo- nomic validity of Finno-Saamic is perhaps not a question of central importance to the recon-struction of Saami linguistic prehistory; it is in any case clear that Finnic and Saami split off from a common parent language regardless of whether this proto-language was ‘Finno-Saa-mic’ or some more inclusive branching from which also some other West Uralic languages have diverged.

70 Ante Aikio

On the other hand, it is equally clear that Pre-Proto-Finnic and Pre-Proto-Saamihave deve-loped in close geographic proximity, as otherwise they could not show the signs of prolonged language contact on all levels of language. Thus, while Finno-Saamic might not be a valid genetic grouping, it still is a valid areal grouping – in Helimski’s (1982) terms an ‘areal-gene-tic unit’, i.e. a linguistic subgroup which has only limited evidence of status as genetic node but shows signs of extensive areal interaction. The status of Finno-Saamic as an areal-genetic unit is a fact that must have a specific historical explanation.

3. The areal context of Pre-Proto-Saami

Even though we do not know exactly how Pre-Proto-Saami separated from other early western Uralic languages, we can try to reconstruct its areal context soon after its emergence. Once Pre-Proto-Saami had become established as a distinct dialect or language spoken in its own speech community, its speakers have been in contact with neighboring groups speaking both genetically related and unrelated languages, and traces of these contacts can be recovered by the comparative method and etymological analysis.

Before we can review the evidence of interaction between Pre-Proto-Saami and other con-temporaneous language forms, the term itself needs clarification. The path of linguistic inno-vations that led from Proto-Uralic to Proto-Saami consists of many subsequent periods of language change. The most conspicuous of these periods of change involved a complete re-organization of the Uralic vowel system, which serves as a useful criterion for differentiating a Proto-Saami stage of linguistic development from a Pre-Proto-Saami one.

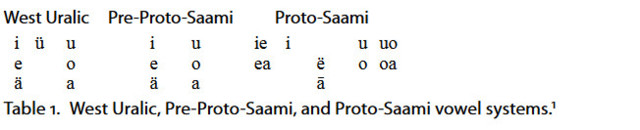

As seen in Table 1, Pre-Proto-Saami had a conservative vowel system which only minimally differred from its ancestral West Uralic vowel system, from which also the Finnic and Mord-vin languages derive. In Proto-Saami, however, the vowel system had developed into a radi-cally different form through a process which can be called the ‘Great Saami Vowel Shift’ (cf. the ‘Great Vowel Shift’ that has taken place in English). A detailed description of the various substages of this process can be found in M. Korhonen (1981: 77–125) and Sammallahti (1998: 181–189).

This reorganization of the vowel system is notable in several respects. First, the development was a complex one, as it consists of a large number of individual sound changes of the shift, split, and split-merger type. Second, it was also radical in the sense that it resulted in a complete redistribution of the vowel space: no single vowel in the Pre-Proto-Saami system remained unaltered. Third, in terms of linguistic typology, the resulting Proto-Saami vowel system is a highly atypical one, especially in contrast to the unremarkable six-vowel system of Pre-Proto-Saami.

71 An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory

That such a complex and idiosyncratic series of changes in pronunciation was completed with near 100% regularity implies that it took place in a relatively compact and tight-knit speech community. In other words, the language must have been spoken within a relatively limited geographical area until the Great Saami Vowel Shift was completed.

For the purposes of this paper Pre-Proto-Saami can be defined as the ancestral form of Saami languages that had already diverged from its Uralic sisters, including Finnic, but which had not yet undergone the Great Saami Vowel Shift. In practice, of course, the vowel shift consis-ted of various substages, and in detailed linguistic analyses one can make more fine-grained distinctions between various proto-stages of Saami, but these are hardly relevant for what will be argued below.

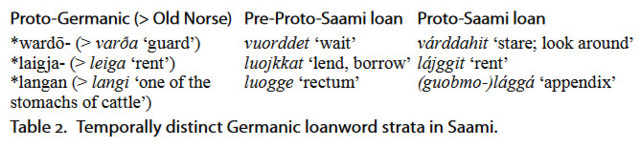

The usefulness of the Great Saami Vowel Shift for reconstructing Saami linguistic prehistory lies in the fact that it provides a rather good criterion for determining at which stage various loanwords have been adopted. Certain loan-words show the effects of this vowel shift and must thus have been present in Pre-Proto-Saami already,whereas others do not and must con- sequently have been adopted only after the shift. For example, in Germanic loanwords adop-ted before the vowel shift, we can see the development of Pre-Proto-Saami *a to Proto-Saami *uo, whereas in later loans from the same source a different reflex is found. This is illustrated by the following Lule Saami word duplets consisting of two temporally distinct borrowings of the same Germanic word:

RJK: Kaikki nämä lainat ovat baltista.

There are three source language groups from which loanwords are known to have penetrated into Pre-Proto-Saami in significant numbers:Baltic,Germanic, and Finnic. A notable problem for the analysis of Finnic loanwords is that they are notoriously difficult to stratify and date; it is often quite hard to find unambiguous criteria that would reveal whether a particular loan was adopted to Pre-Proto-Saami, Proto-Saami, or even later into the already differentiated Saami languages. In large part this is due to the phenomenon of ‘etymological nativization’ mentioned in the previous section and discussed in more detail in Aikio (2007a). Especially as regards vowels, even recent loans between Saami and Finnic have often been adapted to the regular sound correspondences displayed by shared Uralic vocabulary. This often makes it impossible to solve at which stage of language development the word was borrowed, and occasionally one even cannot determine whether the word was borrowed at all or inherited from a common parent language instead.

72 Ante Aikio

This is an unfortunate situation, as it renders the majority of etymological material essentially useless for the dating of Finnic-Saami loan contacts. However, it appears that the regular vo-wel correspondence Finnic a ~ Saami uo never became a model for etymological nativization (Aikio 2007a: 36), and hence it serves as a valid criterion for identifying Finnic loans that entered the language before the Great Saami Vowel Shift. The problem, then, is to distinguish loans showing this vowel correspondence from cognate items due to common inheritence, and this can only be done if the word shows a consonant correspondence that reveals it as a loan. Even though such a limitation rules out the vast majority of all possible sound combinations, at least two such etymologies can be found:

SaaN buošši ‘ill-tempered (of a woman) =pahansisuinen (nainen)’< PSaa *puošē < Pre-PSaa *paša < Pre-PFi *paša (> PFi *paha > Fi paha ‘bad, evil’). – The word must be a loan, as it displays the secondary Pre-PSaa sibilant *š; an inherited cognate of Fi paha would have undergone the change *š > *s and thus developed into the form **buossi in North Saami. The loan original must still have had the sibilant *š; the Finnic change *š > *h is even younger than the PSaa vowel shift *a > *uo, ...

RJK: Tämä on kirkollinen myöhäinen (n. 1000 j.a.a.) ruteenilaina eli slaavin kautta tuleva balttilaina sanasta ven. plohoi, liett. blogas, toinen muoto laho: h EI tule š:stä vaan "ukraina-laisesta" g:stä tai venäläisestä h.sta (x) sanasta plohoi = paha, huono, liettuan blogas = mt.

Saamen buošši on jotakin muuta perua (böse?). Mahdollisesti liittyy liettuan verbiin besti (beda, bedo) = puskea (sarvin tmv.), pistää (keihäällä), kaivaa

... as revealed by the later loan SaaN láš’ši ‘lean = laiha ’ (< PSaa *lāššē < Pre-PFi *laiša > Fi laiha ‘lean’).

RJK: Balttilaina, samaa kuin liettuan liesas = laiha, viron lahja = laiha (liemi)

SaaN buolža ‘moraine ridge’ < PSaa *puolčë < Pre-PSaa *palći < Pre-PFi *palći (> PFi *palci > Fi palsi ‘a hard layer of soil or clay, especially in the bottom of a lake’). – The word must be a loan, as it displays the Pre-PFi change *ti > *ći; the actual inherited cognate of the word is SaaL buollda ‘mountain side’ (< *palti). These etymologies are important as they reveal the existence of loan contacts between Pre-Proto-Saami and Pre-Proto-Finnic.

RJK: Tämä on taattu balttisana. Tämä myös taipuu vanhalla e-kaavalla, jolla yksikään ainoa germaanilaina ei taivu.

The fact that we can find even two examples of such loans by applying highly exclusive pho-nological arguments implies that in reality many words must have been borrowed in the same period; usually there just are no criteria for determining whether a particular loanword dates back to this stage.

It is much more illuminating to analyze loans adopted to Pre-Proto-Saami from genetically unrelated contact languages, in particular Baltic and Germanic which are known to have ex-tensively contributed to the lexica of Saami and Finnic languages over long periods of time. The oldest strata of Baltic and Germanic loanwords in Saami are superficially similar in that both are to some extent shared with Finnic, and that Finnic possesses more old borrowings from these sources than Saami does.

The fact that Saami partially shares its oldest Baltic and Germanic loans with Finnic, sho-wing a much stronger influence from these languages,has given rise to the idea that the oldest loans from these sources were not in fact adopted tom Saami independently but spread there via Finnic. This was suggested already by Vilhelm Thomsen (1869), the pioneer of Germanic and Baltic loanword studies.

73 An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory

Recently a somewhat similar stance has been cautiosly supported by Kallio (2009: 34, 36), who notes the possibility that the majority of Proto-Baltic and the oldest Proto-Germanic loans in Saami were mediated by Pre-Proto-Finnic. On the other hand, Koivulehto (1988; 1999) has emphasized that Pre-Proto-Saami appears to have adopted independent Germanic borrowings already at its earliest stages.

A closer inspection of the etymological material reveals a notable difference between the dis-tributions of Baltic and Germanic loans. If we exclude borrowings which were certainly or at least very probably mediated by Finnic, there seem to be 32 old Baltic loanwords in Saami. 2

A conspicuous feature of the material is that nearly all of these words have a cognate in Fin-nish; only eight words (faggi,giehpa, johtit, leaibi, loggemuorra, riessat, vietka,saertie) have a distribution limited to Saami.The number of Proto-Germanic loans is twice as high,63 words. 3 Of these slightly over a third, 23 words, have a possible cognate in Finnic; even in many of these cases there is evidence suggesting that Finnic item was separately borrowed (Aikio 2006: 10–13, 39).

Thus, we have three independent findings regarding loanword stratification:

a) Pre-Proto-Saami had adopted loanwords from Pre-Proto-Finnic

b) Pre-Proto-Saami had a stratum of Proto-Baltic loanwords that was for the most part shared with Pre-Proto-Finnic

c) Pre-Proto-Saami had a stratum of Proto-Germanic loanwords that was for the most part not shared with Pre-Proto-Finnic

These results can be interpreted in several ways.One possible scenario is that the Baltic loan-words are on average older than the Germanic ones, and were adopted into a ‘Finno-Saamic’ proto-language before its separation to Pre-Proto-Finnic and Pre-Proto-Saami; at the same time, some Germanic loans were also adopted. After the language split, then, the Baltic con-tacts of Pre-Proto-Saami would have ceased whereas the Germanic contacts would have be-come more intensive. Pre-Proto-Finnic would have continued to develop under heavy influ-ence of both Baltic and Germanic, which is reflected as a significantly larger number of old Germanic and Baltic loans in the Finnic languages.

While such a scenario is in itself possible, the problem is that we do not really have clear ta-xonomic evidence for the reality of a distinct ‘Finno-Saamic’ proto-language. Hence, invo-king such a proto-language to explain the distributional peculiarities of Germanic and Baltic loans smacks of circular reasoning.If one presumes instead that the Finno-Saamic areal-gene- tic unit was a dialect continuum, one can posit the hypothesis that the different distributional profiles of Proto-Baltic and Proto-Germanic loans reflect not two periods of borrowing, but instead two different geographical positions of the source languages in relation to Pre-Proto-Finnic and Pre-Proto-Saami; as regards Germanic borrowings,this conclusion has been drawn by Koivulehto (1999). As argued in Aikio (2006: 45), the following picture suggests itself; the arrows indicate major pathways of loanword adoption:

74 Ante Aikio

Thus, it seems likely that ‘Finno-Saamic’ was a dialect continuum instead of a proto-lan-guage, and that different speech communities within this continuum had different geographic patterns of interaction with outside groups. Both the speakers of Pre-Proto-Saami and Pre-Proto-Finnic have been in independent contact with Germanic speakers,even though a part of the loanwords have diffused between the dialects and eventually become a part of both Fin-nic and Saami lexicon. On the other hand, only the speakers of Pre-Proto-Finnic dialects had any significant contacts with Baltic-speaking groups, and the Baltic loans found in Saami have secondarily diffused through the dialect continuum. Such an account explains why nearly all Baltic loans in Saami are shared with Finnic.

Against this interpretation one might say that there are, after all, a few Baltic loans in Saami that do not have a cognate in Finnish (Koivulehto 1992a). Their number is, however, only a quarter of all loans, 8 out 32 cases.4 Thinking statistically, such a fraction does not serve as proof of any independent contacts between Pre-Proto-Saami and Baltic, because it cannot be assumed that Finnish would have retained 100% of the vocabulary of Pre-Proto-Finnic. It is predictable that there also are some Baltic loans which were mediated via Pre-Proto-Finnic to Pre-Proto-Saami, but later disappeared in Finnic itself. The figures imply a survival rate of roughly 75% in Finnish for loans from this period, which actually seems rather high.

One must note, though, that there also appear to be three Baltic loans in Saami which lack a cognate in Finnic and which, for phonological reasons, could not even in theory go back to a common Finno-Saamic proto-form as they display the secondary Proto-Saami sibilant *š: SaaN šielbmá ‘threshold’, šear’rát ‘shine brightly’ and šuvon ‘good dog’ (Sammallahti 1999: 79; Aikio 2009: 199–200; Kallio 2009: 35). However, even in these cases one cannot prove that they were not at a somewhat later stage borrowed from Pre-Proto-Finnic forms which subsequently became lost in Finnic. 5

In the case of one word such an argument runs into difficulties, however. The word for ‘alder’ has apparently been borrowed from Baltic in two different phonological shapes: Pre-Proto-Saami *lejpä (> SaaN leaibi ‘alder’) vs. Pre-Proto-Finnic *leppä (> Fi leppä ‘alder’). 6 In this case the diffusion hypothesis is perhaps excluded due to the distinct shapes in Finnic and Saami. However, it would be daring to draw far-reaching conclusions on the basis of one etymology only.Even if the word for ‘alder’ is a relic of direct interaction between Pre-Proto-Saami and Proto-Baltic speakers,the scarcity of the etymological evidence suggests that these contacts have been of mere minor significance. It is still clear that Pre-Proto-Saami remained outside the sphere of any major Baltic influence, which starkly contrasts with the evidence of the heavy impact of Baltic on Pre-Proto-Finnic.

75 An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory

Recently Häkkinen (2010b) has proposed the following prehistoric interpretation of the Proto-Baltic and Proto-Germanic loanwords in Saami:

“Since the end of the Bronze Age or the beginning of the Iron Age the contacts between Saami and Germanic have intensified, whereas the contacts between Saami and Baltic have decreased in the Iron Age, which in terms of geography can be interpreted so that the Early and Mid-Proto-Saami-speaking area ended up closer and closer to the sphere of Germanic influence or even geographically spread or moved towards it, and on the other hand the speaking area of Finnic may have expanded to cut off the direct contacts between Saami and Baltic.” (Häkkinen 2010b: 57; translated from Finnish.)

Our interpretation obviously turns out to be different, if we accept the conclusion that there never even was significant direct contact between Baltic and Pre-Proto-Saami speakers in the first place. In that case it is unnecessary to postulate any major changes in the speaking areas of proto-languages at this stage. We can instead assume that nearly all of even the oldest Baltic loanwords in Pre-Proto-Saami were adopted via Pre-Proto-Finnic, but the difference between the sound systems of these dialects was still so small at that point that we cannot tell these loanwords apart from cognate items by phonological criteria.

Therefore, it would appear that the contacts between Saami and Baltic never ceased because they never even really began. Baltic loanwords have diffused to the Saami part of Finno-Saamic at many periods, often significantly later than the Finnic word itself was originally borrowed from Baltic. The older the diffusion the more archaic are the phonological features the Saami word exhibits, and the oldest diffused words cannot be told apart from true cognate items. On the basis of the reflexes of Baltic *š, for instance, we can distinguish between three stages of borrowing:

1. The earliest loans show the change *š > *s in Pre-Proto-Saami (e.g. SaaN suoidni ~ Fi heinä ‘hay’ < *šajna, cf. Lithuanian šienas ‘hay’).

2. Younger loans were borrowed after the introduction of secondary *š in Pre-Proto-Saami, but before the Finnic change *š > *h (e.g. SaaI šišne ‘tanned leather’ < Pre-PFi *šišna > Fi hihna ‘leather strap’; cf. Lithuanian šikšna ‘tanned leather’).

3. The most recent borrowings reflect Finnic h < *š (e.g. SaaN heaibmu ‘tribe’ < Fi heimo < Pre-PFi *šaimo, cf. Lithuanian šeima ‘family’).

In addition to Proto-Baltic and Proto-Germanic loans, it has been proposed that even earlier Indo-European loans were independently borrowed into Pre-Proto-Saami; these would stem from ‘Northwest Indo-European’, an early predecessor of Germanic and Balto-Slavic langua-ges (Koivulehto 2001). If this interpretation is correct, it implies that the dialectal differen-tiation between Pre-Proto-Saami and Pre-Proto-Finnic has very deep roots. There are reasons for uncertainty, however.

76 Ante Aikio

The hypothesis is based on a rather small number of etymologies; according to Sammallahti (2011: 209) there are fifteen such independent loans in Saami. As there are many more ancient Indo-European loans that Saami shares with Finnic or other West Uralic languages, at least a part of the fifteen cases can certainly be explained as words whose cognates have become lost elsewhere.

4. Proto-Scandinavian loanwords and the dating of Proto-Saami

As the Pre-Proto-Saami language transformed into Proto-Saami, its contacts with Germanic language varieties seem to have intensified. There is a very extensive stratum of loanwords adopted from Proto-Scandinavian to Saami, which provides an excellent basis for reconstructing the Saami-Scandinavian contact networks in this period.

The Proto-Scandinavian loans in Saami have a long research history, which in its early stages was characterized by a polarized debate on their very existence. Qvigstad (1893) initially wanted to deny that altogether, whereas Wiklund (1918) claimed their number was as high as 600. Later research revealed Qvigstad’s original position as false and Wiklund’s figure as greatly exaggerated.In his critical assessment of the phonological criteria for Proto-Scandina- vian origin Sköld (1961) found it questionable whether even 200 loans could be shown to date back to the Proto-Scandinavian phase. Since Sköld’s study there have been many advan-ces in the field especially due to the extensive loanword research conducted by Koivulehto (e.g., 1992b; 1999). However, no up-to-date synthesis of the stratification of Scandinavian loanwords is available, and Sköld’s (1961) monograph on the topic is outdated.

The study of Proto-Scandinavian loans is a rich source for Saami linguistic chronology, be-cause Proto-Scandinavian, despite being a primarily reconstructed language, is also fragmen-tarily attested in the Early Runic inscriptions.Because many Scandinavian sound changes can be given absolute datings with the help of runic material, this allows us to provide absolute terminus ante quem datings for many loanwords in Saami. The forms of Proto-Scandinavian loans in Saami mostly seem to correspond to the phonology of the language attested in Early Runic roughly in the period 200–500 AD, and by 700 AD at the latest the Scandinavian lan-guage varieties had undergone remarkable sound changes (Nielsen 2000) after which many of the attested Saami forms could not have been borrowed. The analysis and more exact dating of individual sound changes and loanwords are naturally complicated issues.

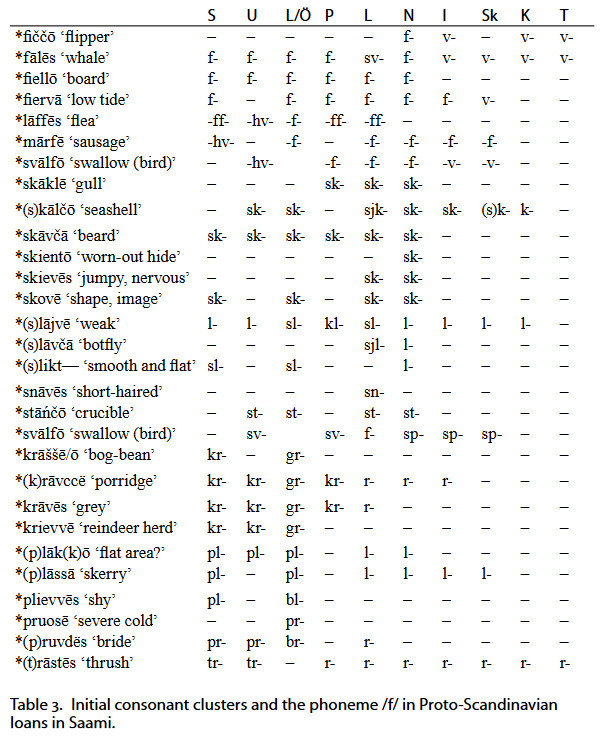

Saami linguistic chronology can be correlated with the Scandinavian one by the help of loan etymologies which can be dated as Proto-Scandinavian and at the same time exhibit important Saami phonological innovations. The Proto-Scandinavian loanwords in West Saami languages show certain phonological features that are mostly absent in East Saami. Especially notable is the treatment of word-initial consonant clusters and the phoneme /f/, both of which were originally foreign to Saami.

77 An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory

Both features occur throughout the West Saami area even in old loans deriving from Proto-Scandinavian. In individual words these features have often secondarily spread to Inari Saami and sometimes even to Skolt Saami via North Saami influence, but the easternmost languages Kildin and Ter Saami seem to have acquired initial consonant clusters and /f/ only very recently through borrowings from Russian. The following words serve as examples:

● SaaS faaroe, U fárruo, P faarruo, L fárro, N fárru, I fááru ‘party, company (of travellers)’, Sk väärr, K vārr, T varr ‘trip, journey’ (< PSaa *fārō ~ *vārō) < PScand *farō > ON fǫr ‘journey’. – The Inari form with f- has been influenced by North Saami.

● SaaS skaaltjoe, U skálttjuo, L sjkálltjo, N skálžu, I skálžu, Sk skälǯǯ ~ dial. kälǯǯ, K kāllǯ ‘seashell’ (< PSaa *skālčō ~ *kālčō) < PScand *skaljō > ON skel ‘shell’. – The Inari and Skolt forms with sk- have been influenced by North Saami.

It is worth the while to examine the distribution of these phonological features in those loans which can be dated as Proto-Scandinavian. The data are presented in Table 3; the actual etymologies in question are listed in an appendix to this paper. The material shows an interesting pattern. In all West Saami languages, forms with the consonant /f/ and initial clusters of the type *sC- are found. However, initial clusters of the type stop + liquid (pl-, pr-, tr-, kl-, kr-) show a narrower distribution, as they are confined to South, Ume, and Pite Saami.

It is clear that during the Proto-Scandinavian period Proto-Saami had already dialectally diversified, and that the dialects exhibited different patterns of loanword nativization. On the basis of nativization patterns in Scandinavian loans one can distinguish between three proto-dialects at this period:

● The southwest dialect (> South, Ume and probably also Pite Saami), 7 which had adopted:

● word-initial consonant clusters of the type *sC-

● word-initial consonant clusters of the type stop + liquid

● the phoneme /f/

● The northwest dialect (> Lule and North Saami),8 which had adopted:

● word-initial consonant clusters of the type *sC-

● the phoneme /f/

● The east dialect (> Inari, Kemi, Skolt, Akkala, Kildin, and Ter Saami), which had adopted none of these features.

In addition to the phonological differences, the table illustrates how the occurrence of Proto-Scandinavian loans is heavily concentrated in the West Saami area. In East Saami their number is smaller, and only few are found in Kildin and Ter Saami on the Kola Penisula. This also points to the conclusion that Proto-Saami was in fact a diffuse dialect continuum at the time of Proto-Scandinavian contacts, and that the loans were adopted in the West Saami area from which a part of them diffused further east via dialect borrowing. We can, indeed, verify this interpretation by onomastic evidence. Along the Norwegian coast there are scattered Saami place-names which have been convincingly explained as loans from Proto-Scandinavian; the southernmost of these are found in the South Saami area.

78 Ante Aikio

The clearest examples are South Saami Måefie (Mo i Rana) and Mueffie (Mo i Vefsn), which due to their consonant /f/ must have been borrowed from Proto-Scandinavian *mōhw az (> ON mór ‘heath’). Another interesting example is Laakese, the older South Saami name for the Namsen river which is now commonly called Nååmesje. This seems to reflect Proto-Scandinavian *laguz (> ON lǫgr ‘sea, lake, water’, Norwegian

-lågen in river names); the loan must have been adopted before the Scandinavian sound change *z > *r. These as well as several other plausible candidates for Proto-Scandinavian loan names have been discussed by Bergsland (1996). Similar cases are found in the North Saami area as well. The best-known one is the name of the island Máhkarávju (Magerøy) in the extreme north of Norway;

79 An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory

-ávju can only reflect a Proto-Scandinavian form *aujō and certainly not its later Old Norse development ey ‘island’. An apparently previously unnoticed case is the fjord name Vávžavuotna (Veggefjord) on the island Ringvassøy north of Tromsø. Here Vávža- (< PSaa *vāvčë-) seems to reflect PScand *wagja- (> ON veggr ‘wedge’). The treatment of the consonant cluster is the same as in well-known borrowings such as SaaN ávža ‘bird-cherry’ < PScand *hagja- (> ON heggr ‘bird-cherry’).

Hence, it can be concluded that Proto-Saami had dialectally diversified before the end of the Proto-Scandinavian phase ca. 500–700 AD, and that in Scandinavia its dialects were already spread over roughly the same area where Saami languages have been spoken in historical times. Proto-Scandinavian loans thus yield a terminus ante quem for the presence of Saami languages in their current areas in Scandinavia. On the basis of the dating of individual sound changes such, such as *z > *r, Heikkilä (2011: 68–69) concludes that borrowed place-names demonstrate the presence of Saami languages in Scandinavia by 500 AD at the latest; the same conclusion was presented by Bergsland (1996) already.

Proto-Scandinavian loanwords also provide ample material for the reconstruction of the social setting of these contacts. This aspect has not gained very much attention in newer studies on the topic, and a thorough analysis of the material from a semantic and cultural perspective would be highly desirable.

However, already a cursory application of the classical ‘Wörter und Sachen’ approach reveals notable patterns. The following six cultural domains are especially interesting (the cited forms are North Saami unless otherwise indicated):

sea and seafaring

áhpi ‘open sea’, bárru ‘wave’, fiervá ‘beach revealed by low tide’, ákŋu ‘thole’, dilljá ‘rowing seat’, gielas ‘keel’, rággu ‘boat rib’, gáidnu ‘rope for pulling a boat or a net with’, láddet ‘land a boat’, sáidi ‘saithe’, sildi ‘herring’, fális ‘whale’, fihčču ‘seal’s flipper’, skálžu ‘seashell’, skávhli ‘gull’, gáiru ‘great black-backed gull’

domestic animals

gussa ‘cow’, gálbi ‘calf (of a cow)’, sávza ‘sheep’, láppis ‘lamb’, gáica ‘goat’, vierca ‘ram’, L hábres ‘ram’, mielki ‘milk’, lákca ‘cream’, ullu ‘wool’, ávju ‘meadow hay’, gáldet ‘castrate’

agricultural products

rákca ‘gruel’, láibi ‘bread’, gáhkku ‘flatbread’, gordni ‘grain’ iron ákšu ‘axe’, niibi, ‘knife’, ávju ‘edge of a blade’, dávžat ‘whet’, 9 stážžu ‘crucible’, áššu ‘glowing coals’ (< *‘hearth (in a smithy)’), I ävli ‘chain’

fur trade

skieddu ‘old and worn hide’, ráhččat ‘spread a skin to dry’, 10 L skidde ‘skin (as merchandise)’, L árre ‘hair side of a hide’, L hálldat ~ álldat ‘scrape a hide clean’, S maarhte ‘marten’

marriage and family

dievdu ‘adult man, married man’, gállis ‘husband, old man’, máhka ‘a man’s brother-in-law’, S provrese ‘bride’, S daktere ‘married daughter’, árbi ‘inheritance’

80 Ante Aikio

The material clearly shows that seafaring, domestic animals and agricultural products were introduced to the Saami via Proto-Scandinavian speakers. It is interesting that words for the most common domestic animals and basic agricultural products were borrowed from Proto-Scandinavian, as there is little evidence of these animals actually having been kept by the Saami so early, let alone that the Saami would have had fields for growing grains. This suggests the existence of a trade network, in which the Saami acquired animal and agricultural products as well as iron implements from Proto-Scandinavian speakers.

This means that the Saami must have possessed means to purchase these products. Interestingly, there are also a few borrowings which seem to be connected with animal furs and hides. As it is known that Scandinavia provided furs for Ancient Rome already in the 1st century AD (Jones 1968: 23), it is not a great logical leap to connect the Saami in Scandinavia as a producer node in this trade network. This has already been proposed on the basis of archaeological evidence, and it is in any case known from the historical record that the Saami later played a key role in the Scandinavian fur trade (Zachrisson & al. 1997: 228–234). In this regard, it is significant that also words related to marriage and in-laws have been borrowed from Proto-Scandinavian. This suggests the occurrence of mixed marriages, and one can speculate that marriages between Scandinavian men and Saami women could have served as a way of securing trade relations, as has been suggested by Storli (1991). A similar institution, in fact, developed in the North American fur trade run by the English and the French, giving rise to the Métis ethnic group of mixed European and Native American ancestry (van Kirk 1980).

5. The Palaeo-Laplandic substrate in Saami

Proto-Scandinavian loans demonstrate the existence of a Saami-Scandinavian contact network in Lapland already in 500 AD, but they do not reveal how far arlier we can trace the history of Saami languages in the region. Many scholars have tended to see the Saami roots of Lapland as much older, going back to the Early Bronze Age (e.g. Carpelan & Parpola 2001) or the Stone Age (Sammallahti 2011). Some have even entertained the fantastic notion that some of the first settlers of Lapland after the last Ice Age could have been linguistic ancestors of the Saami – for example Halinen (1999), who has later (2011) changed his opinion, however.

In a methodological perspective it is interesting to note that the varying early datings are typically justified by the same type of argument: it is common to claim that the ‘archaeological continuity’ in a given region – i.e., the lack of evidence for some kind of cataclysmic event in the archaeological record – suggests that no language shift has taken place. This is, however, a non sequitur argument, because language shift is not the type of social process that needs to be accompanied by radical change in material culture (cf. Gal 1996).

81 An essay on Saami ethnolinguistic prehistory

Häkkinen (2010a) has demonstrated the weakness of arguments based on archaeologicalcontinuity, and emphasized that linguistic datings must be established via linguistic and not archaeological methods. Hence, the right question to ask is whether there are any actual linguistic data that could establish a terminus post quem for the presence of Saami languages in Lapland.

According to an old theory formulated by Wiklund (1896: 7–14), the Saami had earlier spoken a non-Uralic language he called ‘Protolappisch’, which they supposedly had then switched to a Uralic one adopted from ancestors of the Finns. While the idea was initially popular, it later fell into disfavor among linguists, not least because Wiklund was never able to produce any convincing evidence of the former existence of his hypothesized ‘Protolappisch’ language.

In retrospect it is also easy to see the theoretical shortcomings of the model that derive from the Zeitgeist in the turn of the 20th century: linguistic and racial origins were thoroughly confused, whereas ethnic categories were seen as everlasting and unchanging. In Wiklund’s view the Saami had always been Saami regardless of whether they had spoken a Saami language or some unknown non-Uralic language. 11

While Wiklund’s theories of Saami prehistory were clearly wrong in almost all the details, his basic hypothesis of a language shift still remains completely plausible. There is a very simple reason to assume a priori that such a shift must at some point have occurred: while it is known that there has been continuous human inhabitation in Lapland for some 12 000 years, the Uralic proto-language itself can hardly be dated older than some 4000 – 6000 years BP (cf. Kallio 2006). Thus, instead of asking whether a language shift from unknown languages to Saami has occurred in Lapland it is more rational to try to find out when it did occur.

In retrospect it is not surprising than Wiklund could not present any reasonable linguistic evidence in support of his ‘Protolappisch’ theory. Saami historical phonology and etymology were still so poorly understood in his times that it would simply not have been possible to reliably identify traces of disappeared languages in Saami. Now the situation is very different, as Saami historical linguistics has developed into a highly advanced field of research, and also word origins have been extensively studied. This provides a much more solid foundation for searching for the elusive traces of lost languages of Lapland. To avoid the confusing ethnic implications of Wiklund’s ‘Protolappisch’, these lost languages are best called ‘Palaeo-Laplandic’; we know absolutely nothing of the ethnic identities of the people who spoke these languages, except that they certainly did not identify themselves as ‘Saami’.

Before proceeding to examine concrete linguistic evidence, however, it is worth the while to ponder how a language shift actually happens. On the level of a local community the process of language shift is typically both rapid and irreversible. The shift of the language of daily communication usually occurs over the course of no more than a few generations. As the speech community adopts a new language, bilingualism first develops, and only rarely this will remain a steady state. More probably the process proceeds to a stage where nearly all

young adults start speaking the target language to children, and at this point it is

Kommentit