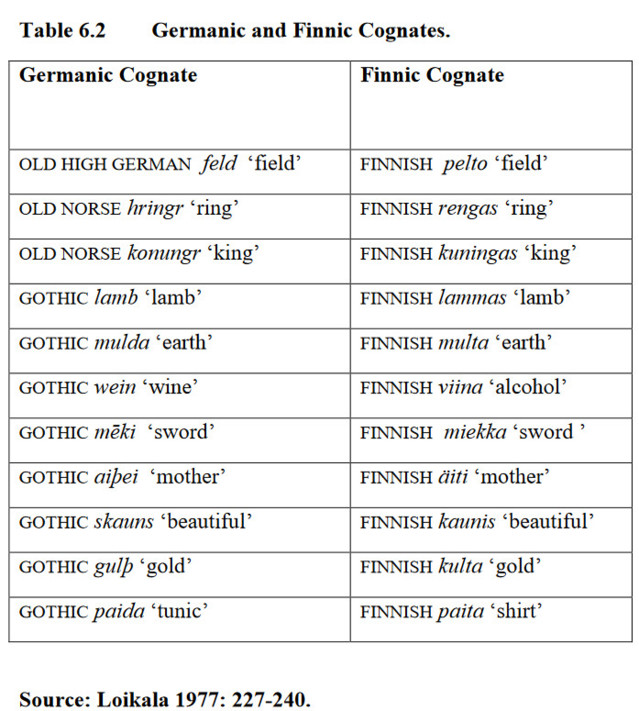

Väittelijä Michel Robert St.Clair, University on California Berkeley, katsoo germaani-sen kielikunnan muodostuneen eristyksissä (kanta)indoeuroopplaisista ympäröivien muiden kielikuntien kuten pohjois-afrikkalaisen (haamilaisen?),baskilaisen ja vähem- mässä määri suomalais-ugrilaisen vaikutuksesta. Länsieurooppalaisten kielitieteilijöi-den laajasti jakamaa näkemystä,että germaanisen kielikunnan muodostumisalue olisi ollut pohjois-Euroopassa, esimerkiksi pohjois-Saksassakaan, väittelijä pitää har-haanjohtavana (putative). Ensimmäistäkään KANTAgermaanista lainsanaa väittelijä ei "löydä" koko uralilaisesta kielikunnasta. Sen sijaan hän kelpuuttaa joukon suomen gootti- ja kantaskandinaavilainoja, joista niistäkin osa kuitenkin on varmasti väärin: kuningas (ei ole itägootissa,joka tulee kanta-IE:stä),kaunis (länsibalttia),pelto (kanta-IE:tä).

Väittelijä vertailee kielitieteen kantakieli- ja kontaktiteoriamenetelmiä eikä pidä kum-paakaan kaikeselittävänä.Jälkimmäinen varsinkin vaatii ehdottomasti tukea muualta- kin kuin kielitieteestä.Väittelijä suhtautuu asiallisesti Kalevi Wiikin teoriaan kantager- maanin "uralilaisesta substraatista" - vaikka se yleisesti ottaen tiedetäänkin vääräksi. Y-haplotiedot eivät tue Wiikin hypoteesia - sikäli kuin N-haplo liitetään uralilaiseen kieleen.

Väitöksen varsinainen aihe on genetiikka kielitieteen tukena.

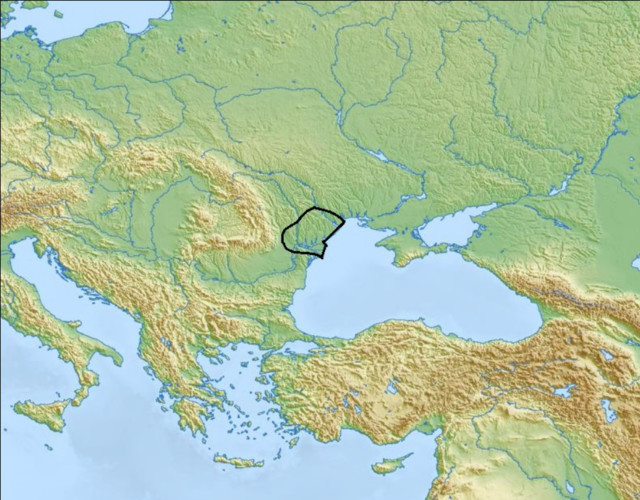

Usatoven kulttuuri 3500 - 3000 e.a.a. saattoi hyvinkin olla germaanin syntypaikka ja myös gootin. Osa gooteista olisi aina pysynyt samoilla paikoilla. Niin sanotussa An-thonyn mallisssa on sitten kyllä muuta puutaheinää - kuten että sotavaunukansojen kielet olisivat olleet kantaindoeurooppaa. Germaanit eivät olleet välttämättä lainkaan mukana sotavaunuekspansiossa.

https://escholarship.org/uc/item/9v44n49p

2012

- St. Clair, Michael Robert

- Advisor(s): Rauch, Irmengard

Abstract

This dissertation holds that genetic data are a useful tool for evaluating contempora-ry models of Germanic origins. The Germanic languages are a branch of the Indo-European language family and include among their major contemporary representa-tives English, German, Dutch, Danish, Swedish, Norwegian and Icelandic.

Historically, the search for Germanic origins has sought to determine where the Ger-manic languages evolved, and why the Germanic languages are similar to and diffe-rent from other European languages. Both archaeological and linguist approaches have been employed in this research direction.

The linguistic approach to Germanic origins is split among those who favor the Stammbaum theory and those favoring language contact theory. Stammbaum theory posits that Proto-Germanic separated from an ancestral Indo-European pa-rent language. This theoretical approach accounts for similarities between Germanic and other Indo-European languages by posting a period of mutual development.

Germanic innovations,on the other hand,occurred in isolation after separation from the parent language. Language contact theory posits that Proto-Germanic was the product of language convergence and this convergence explains features that Ger-manic shares with other Indo-European languages. Germanic innovations, on the other hand, are potentially a relic of an era before language convergence.

Contemporary models of Germanic origins have gravitated towards language con-tact theory to explain the position of Germanic within the European linguistic tapest-ry. However, this theoretical approach is very dependent on the historical record for assessing the influence of language convergence.

This dissertation utilizes genetic data,primarily single nucleotide polymorphism from the human Y-chromosome, for overcoming this inherent weakness of language con-tact theory. With genetic data,the linguist can now assess the influence of prehistoric language convergence by tracing prehistoric population expansions. Based on the available genetic data, the evolution of Germanic during the European prehistory may have been shaped by the convergence of Proto-Basque, Proto-Indo-European, Proto-Afroasiatic, and perhaps to a lesser extent, Proto-Uralic.

Germanic Origins from the Perspective of the Y-Chromosome

By Michael Robert St. Clair

A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor in Philosophy in German

in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley

Committee in charge:

Chair Thomas F. Shannon Montgomery Slatkin

Spring 2012

DEDICATIONDedicated to Dr. David Rood,a great man and Professor of Linguistics at the University of Colorado at Boulder.

ii Table of Contents

Chapter One: Dissertation Overview................................................1

Chapter Two:Germanic Origins:Issues and Approaches................ 2

2.1 Typology..................................................................................... 2

2.2 The Origins of Indo-EuropeanLanguages ................................. 5

2.3 Germanic Origins from the Perspective of Linguistics .............. 7

2.3.1 Comparative Method and Stammbaum Theory............. .........8

2.3.2 Language Contact Theory......................................................10

2.4 Germanic Origins from the Perspective of Archaeology............12

2.5 The “Kossinna Syndrome”.........................................................14

2.6 Germanic Origins from the Perspective of the Y-Chromosome 17

2.7 Chapter Conclusion .................................................................. 19

Chapter Three: Why the Y? The Y-Chromosome as a Tool for

Understanding Prehistoric Migration............................................. 20

3.1 Playing by-the rules................................................................. 20

3.2 Mutation................................................................................... 21

3.2.1 Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms........................................ 22

3.2.2 Short Tandem Repeats......................................................... 24

3.3 Population History..................................................................... 24

3.4 Other Molecular Markers.......................................................... 26

3.5 Chapter Conclusion.................................................................. 28

Chapter Four: Y-Chromosome Haplogroups R, I, N, E, J and G. Population Expansions in the Paleo-, Meso-, and Neolithic ............................. 29

4.1 Haplogroup R........................................................................... 32

4.1.1 The Western European R-Group.......................................... 32

iii 4.1.2 The Eastern European R-Group ................. ..................... 34

4.2 Haplogroup I ............................................................................ 35

4.2.1 Scandinavian I-Group............................................................ 35

4.2.2 Balkan I-Group .................................................................... 36

4.2.3 Sardinian I-Group ................................................................ 36

4.2.4 Central European I-Group..................................................... 37

4.3 Finno-Baltic N-Group ............................................................... 37

4.4 European E-Group ........................................... ...................... 38

4.5 Near Eastern J-Group ............................................................. 41

4.6 Caucasus G-Group ................................................................. 44

4.7 Chapter Conclusion ..................................................................45

5. Chapter Five: The Correlation Between Linguistic and Genetic

Diversity: A Survey of Population Studies .................................. 47

5.1 Africa...................................................................................... 47

5.2 The Role of Gender in Mediating Language Shift .................. 49

5.3 Afroasiatic .............................................................................. 49

5.4 Indo-European Languages .................................................... 49

5.5 Hungarian .............................................................................. 51

5.6 Slavic and Uralic .................................................................... 52

5.7 The Basques .......................................................................... 54

5.8 Tocharian................................................................................ 55

5.9 The Kalmyk............................................................................. 56

5.10 The Gagauz.......................................................................... 56

5.11 The Bakhtiari......................................................................... 57

5.12 Language Shift in Great Britain and Irel ..................... ......... 57

5.13 Language Shift in the Caucasus Region .............................. 59

iv 5.14 Topography as an Explanation of Linguistic and Genetic

Diversity ....................................................................................... 60

5.15 Chapter Conclusion.............................................................. 60

Chapter Six:Evaluating Contemporary Models of Germanic Origins 62

6.1 Wiik´s Uralic Substratum Model......................................... 64

6.2 Anthony´s Kurgan Model........................................................ 67

6.3 Renfrew´s Language-Farming Model..................................... 69

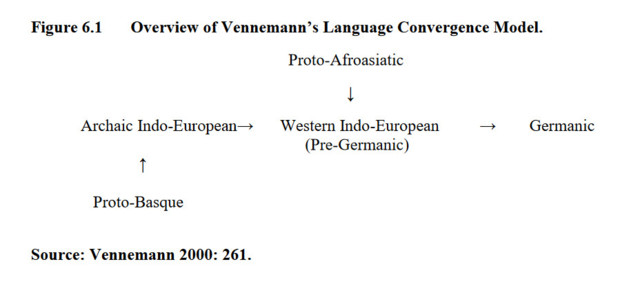

6.4 Vennemann´s Language Convergence Model....................... 71

6.5 Chapter Conclusion............................................................... 73

Chapter Seven: Dissertation Conclusion .................................... 74

Bibliography ................................................................................ 76

Appendices .................................................................................101

Chapter One

Dissertation Overview

My task in this dissertation is to demonstrate that genetic dataare a useful tool for evaluating contemporary models of Germanic origins. To the best of my knowledge, this dissertation represents one of the first attempts by a linguist to utilize genetic data for exploring how the Germanic language family evolved during the European prehistory. This approach to examining Germanic origins reflects that the use of genetic data for such a purpose has only been available within the last decade.

Most of the genetic data provided in this dissertation stem from popu-lation reports that describe world-wide mutational variation found on the non-recombining region of the human Y-chromosome. These re-ports started to appear in the year 2000 following technological advan-ces at the end of the last century that facilitated the identification of molecular markers.

This dissertation is divided into seven chapters.

Chapter Two provides an overview of the traditional approaches to examining the origins of Germanic languages: linguistics and archaeo-logy. The same chapter also provides three reasons why the use of Y-chromosome may have been underutilized.

First, the methodology behind population genetics requires further explication so that the non-geneticist can evaluate the usefulness of this tool.

Secondly, the nomenclature used to Y-chromosome variation has been subject tostandardization and revision since 2000.

Lastly, the source of Y-chromosome data is extremely fragmented, appearing in over 200 population reportspublished in approximately forty different scientific journals.

Chapter Three explicates the methodology for interpreting Y-chromo-some data. The non-recombining region of the Y-chromosome provides a means of tracing prehistoric migration and settlement.

Chapter Four overcomes the problems of inconsistent and revised nomenclature by lumping the Y-chromosome data into ten population expansions during the European pre-history.

Chapter Five provides a survey of population studies that ultimately demonstrate the usefulness of genetic data for the linguist.

In Chapter Six, four contemporary models of Germanic areevaluated utilizing the data from Chapters Four and Five.

The dissertation conclusion, found in Chapter Seven, stresses that contemporary models of Germanic origins are clearly more receptive to language contact theory.

As such, genetic data has become a useful tool for evaluating these models as they are able to overcome an inherit weakness of this theoretical approach to language variation.

With genetic data, the linguist now has a much clearer picture of pre-historic language convergence that may have shaped the evolution of Early Germanic.

Chapter Two

Germanic Origins: Issues and Approaches

2.0 Chapter Introduction.

Perhaps the troubling aspect of any examinationof language origins is that it seems so speculative, that the researcher lacks the security of attested language change as well as the historical record. Neverthe-less, researchers still continue to use the resources at hand to render their best guessas to how Germanic languages may haveevolved in the prehistory. In this chapter,I will discuss the traditional tools for exa- mining Germanic origins, linguistics and archaeology. I will then intro-duce a new source of data for exploring this topic,population genetics. This chapter also presents a section explaining how the search for the origins of Germanic languages has become a controversial topic.

2.1 Typology.

Linguistsclassify the Germanic languagesas a sub-group of the Indo-European language family. The figure below provides an overview of the Indo-European language family. Around 600 Indo-European languages are spoken. Because of space constraints, Figure 2.1Indo-European.

Figure 2.1 focuses on the evolution of the ten main branches of the Indo-European language family. Two of the ten daughter languages, Anatolian and Tocharian, appearing in orange italics, are now extinct. Hellenic (Greek), Armenian, and Albanian are single language bran-ches of the Indo-European language family.Celtic includes Irish,Welsh and Breton.The Italic languages include Latin,as well as the Romance languages, Spanish, Portuguese, French, Italian and Romanian. The Balto-Slavic branch separates into two sub-branches, Baltic and Sla-vic. The Baltic branch consists of Latvian and Lithuanian. Slavic lan-guages include Russian, Ukrainian, Polish, Czech, and Bulgarian. The Indo-Iranian branch includes Persian and Hindi, languages spoken in Asia. (See also Beekes 1995: 11-33 for a more thorough discussion of Indo-European languages.)

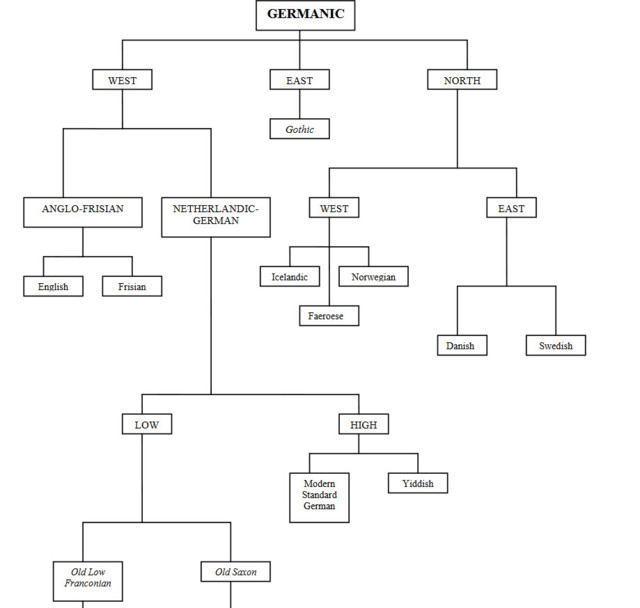

Several languages fall under the classification of “Germanic,” inclu-ding Dutch, Frisian, German, Norwegian, Danish, Icelandic, Swedish, and English, the language of this dissertation.

................Dutch ...............................German

4 Figure 2.2 Germanic.Chart adapted from Pyles and Algio 1993: 68-69.

Figure 2.2 provides an overview of the Germanic branch of the Indo-European language family, reflecting the evolution of Germanic lan-guages from an ancestral Proto-Germanic language. Proto-Germa-nic diverged into three sub-branches, North, West and East Germanic. Modern English and Modern Standard German are West Germanic languages. The term “Proto-Germanic” describes the first Germanic language, which arose in prehistoric times in Northern Europe. Proto-Germanic is not attested in the historical record, but rather based on linguistic reconstruction.

Early Germanic, on the other hand, was first attested 2,000 years ago with short inscriptions found on combs, brooches, drinking horns, spearheads,sword scabbards,shield bosses and other personal items. These inscriptions mostly conveyed a personal name or perhaps some sort of magical incantation using,as a character source,the runic alphabet, also known as futhark. These letters may have been borro-wed from an alphabet used for a non-Germanic language spoken in northern Italy (Todd 1992:120).Although very controversial, some date the oldest Early Germanic inscription to the first century BC, and more specifically the following runic words found on a helmet discovered in Negau on the Austrian-Slovenian border:harigasti teiwa (e.g. Schultze 1986: 329). According to Waterman, scholars differ on the meaning of this inscription; he suggests “to the god Harigast” (1976: 21). Another example of Early Germanic is the Golden Horn of Gallehus, which an example of one the few runic inscriptions not conveying a message rooted in magic or religion. This drinking horn, produced in the fourth century,contains the following inscription:ek hlewagastir holtigar horna tawido. This inscription means “I Hlewagast of the Holting clan made this horn” (Waterman 1976: 22). Part of the significance of this inscription is that it provides a glimpse of Early Germanic syntax and morphology.

The most significant attestation of Early Germanic is the Codex Argenteus,a manu- script copy of the bible written in Gothic, the language of the Goths, one of the Ger-manic tribe. Around 100 BC the Goths left the Germanic homeland and by 300 AD they had migrated to the edge of the Black Sea in modern-day Romania. In 341, Wulfila became Bishop of the Goths. In order to convert his people to Christianity he translated the bible into his native language. Since Wulfila was the first to write in Gothic, he had to create an alphabet,possibly adapting letters from the Runic, Greek and Latin (e.g. Rauch 2003: 4-5). While the original manuscript has disappeared, in the sixteenth century a manuscript copy of Wulfila´s bible, the Codex Argenteus was found in the Abby at Werden in Germany. The document appears quite striking, elaborately ornamented in gold and silver letters on purple vellum. During the Thirty Years War, the codex was taken to Sweden, where it remains today at the University of Uppsala. Other copies of Wulfila´s bible are found elsewhere;the Codex Carolinus in Wolfenbüttel, Codex Ambrosiani and Codex Turinensis in Turin, and Codex Gis-sensis in Egypt (Henriksen and van der Auwera 1994: 2). Meanwhile, the Gothic lan-guage has become extinct, perhaps last spoken somewhere in the Ottoman Empire in the sixteenth century (Rauch 2003: 12). Nevertheless, its importance continues in that linguists consider the language to be the best representation of Proto-Germanic in comparative grammar.

2.2 The Origins of Indo-European Languages.

Since Germanic languages are classified as Indo-European languages, the traditio-nal starting point for exploring the prehistoricdevelopment of Germanic languages is to examine the origins of Indo-European languages.Linguists believe Indo-European languages are not indigenous to the European continent, but rather these languages came to Europe from Western Asia sometime during the prehistory.Today, two competing models of this language expansion have surfaced in the literature. Both models attempt to isolate the putative homeland of the speakers of the Proto-Indo-European languages and explain when they expanded into Europe.

Marija Gimbutas, a Lithuanian archaeologist, proposed the Kurgan conquest mo-del of Indo-European origins in a series of articles she wrote over a forty year pe-riod, ultimately compiled in The Kurgan Culture and the Indo-Europeanization of Europe: Selected Articles from 1952-1993. Her theory is often cited in linguistic texts as offering a plausible explanation of how Proto-Indo-European spread throughout Europe. Trask (1996:360), for example, writes that while he does not find the Kurgan theory totally persuasive, “it is still the best solution we have and it refuses to go away".Gimbutas wrote her final article about the Kurgan conquest in 1993,which was published in 1997. This article, “The Fall and Transformation of Old Europe: Recapi-tulation 1993", reports that the Kurgan culture emerged somewhere in the Volga ba-sin between 5000 and 4500 BC. An identifying trademark of this culture is a unique mortuary practice; they buried their deadin pits, which were then covered with a mound of dirt. In her final article, Gimbutas maintains (1997a: 354) that the Kurgans rode horses and raised herd animals within a patriarchal society. Around 4500 BC the Kurgans became more aggressive and began migrating to the west.

In the area to the west, what Gimbutas often calls “Old Europe,” lived a “Goddess worshiping” culture, whose focus was “the perpetual functioning of the cycle of life, death and regeneration embodied by a central feminine force.” (351). Gimbutas asserts (358) that this culture could not resist the Kurgan invasion of warriors from the east who rode horses and who were better armed. During the conquest of Old Europe, the Kurgans imposed their language, Proto-Indo-European, upon the indige-nous Europeans (364). In her final discussion of the Kurgans, Gimbutas relies in part upon archaeological remains, primarily burial customs and pottery. She also reconst- ructs an Indo-European culture based on the comparative method and comparative mythology. The comparative method (cf. Section 2.3.1below) examines grammatical similarities among attested Indo-European languages and attempts to reconstruct an original Indo-European form using plausible linguistic explanations.

Gimbutas believes that an Indo-European lexicon can be reconstructed, which be-comes the foundation of reconstructing elements of an Indo-European culture, such as social structure and economy.Comparative mythology uses a similar methodology and examines ideological similarities among attested Indo-European-speaking cul-tures, which is then used to reconstruct an Indo-European ideology. Other scholars also cite ideological changes in Europe as additional evidence of a Kurgan invasion (e.g. Fortson 2010: 18-49; Anthony 2007a: 463-466; Beekes 1995: 25-52).

The alternative model of Proto-Indo-European origins, the language-farming model, was proposed by Colin Renfrew, a British archaeologist. In order to understand his model it is necessary to briefly discuss the origins of agriculture in Europe. Following the end of the last Ice Age, about twelve thousand years ago,agriculture arose inde- pendently in seven different areas of the world: Mexico,North America, South Ameri- ca, New Guinea, Sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia, and southwest Asia. The origins of agriculture in southwest Asia are found in what are now Turkey, Syria and Iraq. Star-ting about 10000 BC, people in this area began to cultivate a variety of crops, inclu-ding cereals such as wheat,barley and rye,and pulses such as chickpeas and lentils. They also started to domesticate animals such as sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs. By 6500 BC, farming had spread from southwest Asia to Greece. Within four thousand years this new technology was adopted throughout most of the European continent. From Greece,the spread of farming followed two different routes. One route took far- ming technology along the northern Mediterranean coast, into Italy and finally the Iberian Peninsula.The other route introduced farming in the Balkans, central Europe, and eventually Scandinavia and Britain. (cf. Scarre 2005a: 176-199 and Scarre 2005b: 392-431 for a more thorough discussion of the spread of farming in Europe).

Renfrew published his model of Indo-European origins in 1987, in his book Archaeo-logy and Language: the Puzzle of Indo-European Origins. He proposed (145 - 177) that Indo-European languages were introduced onto the European continent by far-mers who migrated from present-day Anatolia into Europe during the Neolithic era. He asserts that over the course of two thousand years, the descendants of these far-mers migrated into central and western Europe in search of suitable farmland. While the number of farmers involved in the initial migration to Greece was relatively small, their Indo-European speaking descendants were able to colonize southern and central Europe and displace the non-Indo-European speaking hunter-gathers, whose descendants had previously migrated into Europe during the Paleolithic, perhaps 30,000 years prior.

2.3 Germanic Origins from the Perspective of Linguistics.

The linguist Theo Vennemann (2000:234-236) describes a traditional and an alterna- tive approach forexamining the origins of Germanic languages. The traditional ap-proach considers Germanic as a further development of Proto-Indo-European. The alternative model views the origins of Germanic as the product of language contact between two or more languages. The traditional approach follows Stammbaum theory or “family tree” theory, proposed by the German linguist August Schleicher (1821-1868) in his two volume Compendium der vergleichenden Grammatik der In-dogermanischen Sprachen,published in 1861 and 1862. In his Compendium, Schlei- cher provides a taxonomic diagram that posits a chain of events leading to the evo-lution of German, Lithuanian, Slavic, Celtic, Italic, Albanian, Greek, Iranian and Indic from a common Indo-European language. An image of Schleicher‟s Stammbaum, or „family tree‟ is provided in Figure 2.3 below.

Figure 2.3 Schleicher´s Stammbaum.

Figure2.3 Schleicher‟s Stammbaum. Source: Schleicher 1861: 7.

In the first volume of the Compendium (1861) Schleicher cites nume-rous phonological similarities found in German, Lithuanian, Slavic, Celtic, Italic, Albanian, Greek, Iranian and Indic to support his model. In the second volume,Schleicher addresses morphological similarities. Based partly on evolutionary theory, the basic idea behind the Stamm-baummodel is that similarities between languages are accounted for by a common ancestral language and a period of common develop-ment, whereas differences occurred after diverging from the ancestral language.

Language contact theory accounts for similarities between language as a product of borrowing or admixture, and differences as a lack of contact. The theoretical foundation of language contact theory stems from Johannes Schmidt and his 1872 book Die Verwantschaftsver- hältnisse der Indogermanischen Sprachen. In this book, Schmidt voices his disagreement with Stammbaum Theory and its proponent, August Schleicher.

Relying on words and word roots, Schmidt disputes Stammbaum Theory, arguing that similarities in Indo-European languages are not explained by divergence from a single ancestral proto-Indo-European language. He argues that similarities arise from innovations that even-tually spread to neighboring languages. Schmidt proposed a wave model to explain similarities between Indo-European languages.

This model posits that innovations spread due to religious, political, social or other reasons. Nevertheless, the intensity of an innovation loses it strength over distance, similar to the ripple effect when a stone it tossed onto to a lake (27-28).Thus if A, B, C, D, E,F and G represent a continuum of languages over distance, an innovation in language C might extend to languages B and D, but not languages A and E.

In my opinion Stammbaum theory and language contact theory are not necessarily contradictory models of language change, but rather may present complementary approaches to language change and va-riation. I personally view Stammbaum theory as a process that could be labeled “divergence” and language contact theory as “conver-gence.” I would like to see both divergence and convergence brought under a single theoretical umbrella to explain language variation and change. Documented language change would probably reflect that both convergence and divergence drive language variation, and that the influence of each model varies over time within a given area. For example, I suspect that in Germany the number of German dialects increased steadily from the Middle Ages until the Napoleonic Wars as a result of increased political and religious fragmentation, which conforms to a divergence model of change. Following the Napoleonic Wars, I suspect dialect variation steadily decreased asthe result of nationalism, according to a convergence model. Moreover, modern mass-media has probably accelerated the process of convergence.

2.3.1 Comparative Method and Stammbaum Theory.

Clackson´s 2007 book, Indo-European Linguistics, presents, in my opinion, an easy-to-read contemporary treatment of the Stammbaum-model across all the Indo-European languages.This book presents ar- guments for this model using phonological reconstructions, as well as morphological, syntactic and lexical reconstructions. The term “recon-struction” points to a part of the grammar that has never been recor-ded. Thus, standard practice requires the linguist to use an asterisk to show that a form is reconstructed. To help the non-linguist understand the methodology behind linguistic reconstruction, I will turn to phonolo-gical reconstruction and use examples from an introductory linguistics book. This methodology is commonly known as the “comparative method.” Reconstructed phonology starts by assembling cognate sets among attested languages. The term cognate reflects the idea that the meaning assigned to a group of sounds is completely arbitrary.

Consequently, if several languages assign the same meaning to the same sounds, then these languages potentially have a common ancestral language. Consider the paradigm below in the table below.

A linguistic interpretation of the data in Table 2.1 would posit that „man‟, „hand‟, „foot‟, „bring‟, and „summer‟ are cognates in English, German, Dutch, and Swedish, whereas Turkish fails to produce a cognate for these words. Taking this a step further, English, German, Dutch, and Swedish may have diverged from a common ancestor, whereas the ancestral language for Turkish and English is different or far more distant in thepast. Once cognate sets have been assembled, the next step in phonological reconstruction is to seek systematic correspondences. Consider Table 2.2 below.

Here the linguist could posit that the striking similarities found in Spa-nish, Portuguese, Sardinian and French for „female friend‟ resulted from divergence from a common ancestral language and the reconst-ructed Proto-Romance word *amika. Based on plausible phonological rules, the *k in Proto-Romance *amika underwent voicing and frication in Spanish, voicing in Portuguese, and deletion in French, whereas Sardinian retained the voiceless stop (Murray 2001: 326 - 329). The historical record indeed shows that French,Sardinian,Portuguese, and Spanish are a product of Roman conquest. As one would expect, the etymology of the Spanish word amiga finds its origins in Latin, and more specifically the word amīca (Diego 1985:53). However, Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Germanic are not attested in the historical record, and thus reconstruction remains the primary means of determining how these languages may have appeared.

The above discussion of linguistic reconstruction is a simplified example of what actually takes years of specialized training. Additio-nally, even with the comparative method,sometimes the decision as to whether a language is Indo-European may rest with linguistic intuition and consensus with most linguists (Clackson 2007: 3). Nevertheless, the non-linguist has a rough idea of the methodology used to support a Stammbaummodel of Germanic origins, an approach still discussed in the literature (e.g. Ringe 2006).

The strength of the comparative method for reconstructing Proto-Indo-European and Proto-Germanic is found in attested Germanic langua-ges. Throughout the history of Germanic, the evolution of sound change hasbeen regular and systematic affecting entire classes of sounds, not just a few words. For example,in the historical evolution of Old High German to Middle High German, back vowels became fron-ted due to phonological phenomena known umlaut (Waterman 1976: 85 - 86). In the evolution from Middle High German to Early New High German, short vowels in open syllables underwent lengthening (c.f. Waterman 1976: 102 - 103).

Nevertheless, the Stammbaum theory as model of Indo-European ori-gins has its critics. For example, Lyle Campbell (2004: 164-166) lists three objections.

First,this approach assumes a uniform Proto-European language over a vast geographical expanse, from Western Europe to India, without dialectal variation.

Secondly, this approach assumes that ten daughter languages, including Proto-Germanic, simultaneously diverged from Proto-Indo-European.

Finally, this approach assumes that after the daughter languages diverged, the speakers of these languages had no further contact with each other.

In my opinion Campbell‟s argument suggests that Stammbaum theory defies the attested behavior of languages.

2.3.2 Language Contact Theory.

The most recognized proponent of modern language contact theory is probably the linguist Sarah G. Thomason.She (2001:1) defines language contact as “the use of more than language in the same place at the same time". One of the most appealing features of her approach to language contact theory is that the historical record indeed contains numerous examples of language contact induced change. Thomason (2001: 10) emphasizes that “language contact is the norm, not the exception. We would have a right to be astonished if we found any language whose speakers had successfully avoided contacts with all other languages for periods longer than one or two hundred years.”

According to Donald Winford (2003:305-308), modern language con- tact theory presents three possible scenarios or outcomes that may occur when a language comes in contact with another language.

The first scenario posits language maintenance, that a language remains largely intact with the exception of lexical borrowing.

The second scenario posits that language contact may induce lan-guage shift,which states that within a geographic area a new language replaces another.

In the third scenario, language contact may result in the creation of a new language, such as a pidgin or creole. The term pidgin can be ex-plained as a hybrid language that sometimes emerges through com-merce and trade among speakers of different languages. Here, the speech community remains rather small. The definition of a creole is somewhat controversial. For the sake of brevity, I would define creole as a pidgin with a much larger speech community. Creoles also tend to be passed from one generation to the next, whereas pidgins serve a temporary need and then disappear.

Interestingly, all the three language contact scenarios posited by Win-ford are attested in Germanic languages. Modern Standard German provides an example of language maintenance. Standard German has borrowed words from Latin, French and English, yet remains gramma- tically distinct in other areas, such as verb second word order and the strong/weak adjective distinction.

The language history of Ireland supports language shift, the second scenario, where English has almost completely replaced Irish Gaelic, a Celtic language. Finally, even the formation of pidgins and creoles is attested in Germanic.Russenorsk provides an example of a pidgin that arose between Norwegian and Russian sailors in the nineteenth cen-tury (Broch 1927). One example of a creole is Negerhollands, a hybrid language that arose in the Virgin Islands in the eighteenth century, a combination primarily of Dutch and African languages (Rossemand Voort 1996).

One controversial aspect of language contact theory involves what is borrowable. The adoption of new words from other languages,i.e. lexi- cal borrowings, is well attested. Modern English provides one of the best examples. Technically a Germanic language, English has borro-wed heavily from French, Latin and Greek,and to a lesser extent, from Scandinavian, Celtic, Spanish, and Italian (Pyles and Algeo 1993: 286 - 311). However, linguists dispute the degree to which borrowing could affect the structure of language (e.g. Winford 2003: 61-63).

Nevertheless, Thomason (2001:63) takes the position that any linguis- tic feature of a language can be borrowed by another language. She responds to her critics by writing, “various claims can be found in the literature tothe effect that this or that is un-borrowable, but counter-examples can be found (and have been found) to all of the claims that have been made to date".An extreme example of structural change in- duced by language contact is found in Asia-Minor Greek,an Indo-Euro- pean language.As the result of long-term heavy contact with speakers of Turkish, the morphology and syntax of Asia Minor Greek changed considerably. For example, common Greek has subject-verb-object word order. However,in certain circumstances Asia Minor Greek adop-ted the subject-object-verb word order found in Turkish. Perhaps more striking is that some dialects of Asia Minor Greek borrowed Turkish agglutinative morphology (Thomason and Kaufman 1988: 215 - 222).

One potentially huge disadvantage of language contact theory is its heavy reliance on the historical record.Stammbaum Theory (cf. Sec-tion 2.3.1), as the reader may recall, utilizes the comparative method and linguistic reconstruction when the historical record has disappea-red. Nevertheless, I would argue that attested Germanic still leaves traces of language contact induced change occurring before recorded history. One possible area that presents evidence of such change in prehistoric Germanic is the lexicon or vocabulary of Modern German. Scholars of Germanic linguistics (e.g. Vennemann 2000: 241 Water-man 1976:36) estimate that a third of the Modern German lexicon lacks an Indo-European cognate. The authority in defining the non-Indo-European and purely Germanic component of the German lexi-con is Schirmer and Mitzka (1969). Uniquely Germanic words fall with-in three categories:cereal production and animal husbandry, seafaring and fishing, and legal terminology. Schirmer and Mitzka (46 - 50) give the following examples of Modern German words having a Germanic origin: Brot „bread‟, Schaf „sheep‟, Hafen „harbor‟, Dorsch „cod‟, Volk „people‟ and König „king.‟

RJK: Yhtäkään noista sanoista ei ole (itä)gootissa, joka on ainoa tunnettu suoraan kantagermaanille perustuva kieli. Tai sitten jos vastin on, se on erilainen ja merkitsee aivan muuta kuin luullaan.

Sanojen Brot, „bread‟, bröd = leipä jne., katsotaan "tulevan kanta-indo-euroopan juuresta *breug- = keittää, kiehua ym. kuten myös sanojen brew, brygga, brauen = panna olutta.

" ... bröd, fsv. bröþ = isl. brauð (ej i Eddad.), da. brød, fsax. brôd, fhty. brôt (ty. brot), ags. bréad (eng. bread), partic.-bildning till ie. roten bhru, sjuda, jäsa, jfr trak. brỹtos, öl (se brygga 1). Ett annat urgammalt o. i vissa idiom allmännare germ. ord för ’bröd’ är lev.

— Giva stenar för bröd, se sten.

... 1. brygga, vb, fsv. bryggia = no., jfr isl. brugga, mlty. brˆwen, fhty. briuwan, brûwan (ty. brauen), ags. bréowan (eng. brew); egentl, starkt vb, germ. *breuwan, resp. brūwan (med nordiskt gg-inskott som i hugga), av en ie. rot bh(e)ru, avlägset besl. med bröd, brinna, brunn.

2. brygga, sbst., fsv. bryggia, brygga, bro = isl. bryggja, mlty. brugge, fhty. brucca (ty. brücke), av germ. *bruᵹjōn, jämte ags. brycg (eng. bridge) av *bruᵹjō-, med g-inskott av äldre *bruwjō- el. möjl., med gammalt ᵹ av k, av ie. *bru-k-iā; i avljudsförh. till bro; se d. o. Jfr om

ordet WuS 1: 189 (med osäker härledning). "

Kiehua, kääntää myllertää on kuitenkin kantaindoeuroopaksi *wre(ng)- (eikä **bhreng- tmv.). Tästä sanata tulee englantiin mm. wreck = tuhota, romu hylky, hävitys ja wrong = väärä. Suomeen siitä tulee paitsi väärä myös verrata ja virrata, baltin kautta. Liettuaan siitä tulee virti = kiehua, keittää ja virsti (verda) = kääntää, myllertää.

Sana *bred-, *breg- tulee sanasta *wre(ng)-, MUTTA SE EI TULE GERMAANISTA vaan ilmeisimmin TRAAKIASTA, jossa kantaindo-euroopan sanan alku *wr menee muotoon *br tai *pr. Sieltä tulee myös monien IE-kielten "hintaa" tarkottava sana prix, price, pris "vastinta" tarkoittavasta PIE-juuuesta *wreg-, ehkä sama juuri kuin edellä mutta eri yhteydessä. Kantagermaanin perilliseen goottiin siitä PIE-sanata tulee NEGATIIVISTA vastinta, vahingonkorvausta tarkoittava sana *wruggo, joka tarkoittaa mm. "hirttosilmukkaa".

Gootin sana "leipä", joka on samaa juurta kuin suomen sanat leipä ja klimppi, latvian klàips, liettuan kliepas, venäjän hleb:

bread – hlaifs (m. A) < klebas = "ympröinti", (f turns to b in sing. Gen + dat and all plural forms), light ~ = hwaitahlaifs (m. A), brown ~ = swartahlaifs (m. A), wheat ~ = hwaitjahlaifs (m. A)

***

Schaff, sheep englannin mukaan "alkuperältään tuntematon sana, jota ei tavata länsigermaanin ulkopuolella".

The plural was leveled with the singular in Old English, but Old Northumbrian had a plural scipo. It has been used from Old English times as a type of timidity and figuratively of those under the guidance of God. The meaning "stupid, timid person" is attested from 1540s. "

Sana SAATTAA olla ihan (jopa kanta-)indoeurooppaakin ja tarkoittaan "(karvan)kaapimaeläintä". Sama sana (?) *s-kap- (kuurin skapis, ruåtsin skåp, suomen kaappi) tarkoittaa baltissa ja pohjoisgermaanissa "kaapima"- eli HÖYLÄLAUTAA ja sellaisesta tehtyjä huonekaluja ym.

Kantaindoeuroopassa on aivan muu lammas-sana, josta suomeen tulee sekä oinas että uuhi:

ewe (n.)

Old English eowu "female sheep," fem. of eow "sheep," from Proto-Germanic *awi, genitive *awjoz (source also of Old Saxon ewi, Old Frisian ei, Middle Dutch ooge, Dutch ooi, Old High German ouwi "sheep," Gothic aweþi "flock of sheep"), from PIE *owi- "sheep" (source also of Sanskrit avih, Greek ois, Latin ovis, Lithuanian avis "sheep," Old Church Slavonic ovica "ewe," Old Irish oi "sheep," Welsh ewig "hind").

Gootin lamb – 1. lamb = karitsa, luultavasti vasarakirvestä "lämmitettävä eläin", ei selviä luonnossa (siihen aikaan kun syntyy), (n. A) 2. wiþrus (m. U) (only one occurence) 3. *lambamimz (noun) (To eat as flesh)

Pohjoisgermaanin får tarkoittaa "karvaa" ja lienee samaa juurta kuin lainan fiber = säie, kuitu, karva

får, fsv., fda. far - isl. far n. (med s. k. /?-omljud; härtill Fctreyjar, Färöarna, liksom Dalmatien, illyr. Delmatia, till albanes. del’me, får); ett speciellt nordiskt ord, väl av germ. fahaz (dock enl. J. Schmidt *fcéhaz) = ie. *pokos = grek. pökos n., ull; med avljudsformen grek. pékos n., fårskinn med ullen på, formellt - lat. pecus n., genit. -or/s, boskap, särsk. får (motsv. sv. fä); närmast: djur nyttigt genom sin ull; närbesl. med germ. *fahsa-, hår (se f ax e).; till roten i grek. pékö, kammar, kardar, klipper (bl. a. om får), lat. peclo, kammar (jfr penjoar), litau. peszu, pészti, rycka, slita. Hit hör även fsv. ulla f celler, ullpäls, sv. dial. fått, sammanrullad ull, ä. da. fatt, höll. vahl osv., av germ. *fahti-. Alltså, att döma av betyd, ’rycka, slita’ i det litau. ordet, liksom isl. reyfl, avriven ull m. m. (se rov), o. sannol. också ull, ett minne från den tid, då ullen icke avklipptes utan avslets. Ett allmännare spritt ieur. ord för ’får’ är ie. *ovi- i bl. a. lat. ovis - isl. der

***

Hafen „harbor‟, haven

" haff (n.)

also haaf, Baltic lagoon, separated from open sea by a sandbar, German, from Middle Low German haf "sea," from Proto-Germanic *hafan (source also of Old Norse haf, Swedish haf "the sea," especially "the high sea," Danish hav, Old Frisian hef, Old English hæf "sea"), perhaps literally "the rising one," and related to the root of heave, or a substratum word from the pre-Indo-European inhabitants of the coastal regions. The same word as haaf "the deep sea," which survived in the fishing communities of the Shetland and Orkney islands. ",

ruotsin hav,

" hav, fsv. haf = isl. haf, da. hav, mlty. haf (varav ty. haff, strandsjö), mhty. hap, ägs. hcef; av germ. *hafan.; möjl. till *hafjan (- sv. häva); jfr med samma grundbetyd. ägs. holm, hav (se holme). - Ordet har i nord. spr. undanträngt den gamla indoeur. o. germ. stammen mar- (se d. o.). ",

hamn,

" 3. hamn (för fartyg) = fsv. = isl. /ip/7i, da. havn, mlty. havene (> ty. hafen), mhty. habene, ägs. hcefene (möjl. nord.; eng. haven); germ. väl *habnö-; möjl., jämte fhty. havan, kruka (ty. hafen) m., grek. kdpe, krubba, m. fl. till en ie. rot kap, innehålla, omfatta = kap i lat. capio, tager, osv. - Hamnbuse, se buse. "

Nämä sanat seuraavat kantaindoeuroopan (PIE) vesi-sanasta:

| *h₂ekʷeh₂ | water |

Lat. aqua, Welsh aig, Russ. Ока (Oka), Goth. aha, Gm. aha/Ache, Eng. éa; īg/island, Hitt. akwanzi, Luw. ahw-, Palaic aku-, ON á, Goth. aƕa (ahʷa) |

aqua- word-forming element meaning "water," from Latin aqua "water; the sea; rain," cognate with Proto-Germanic *akhwo, source of Old English ea "river," Gothic ahua "river, waters," Old Norse Ægir, name of the sea-god, Old English ieg "island;" all from PIE *akwa- "water" (cognates: Sanskrit ap "water," Hittite akwanzi "they drink," Lithuanian upe "a river").

Sanasta tulevat skandinaavikielten jokisanat, joidenkin linkkien mukaan myös "ap- ja up- joet", mikä ei ole mahdotonta, sillä kʷ voi osin huuliäänteenä muuttua myös p:ksi ja gʷ b:ksi aivan kuten myös iranilaisissa kielissä ja joskus myös kreikassa. Näin ilmeisesti tapahtui myös germaanikieleksi oletetussa länsigootissa.

- Alla oleva etymoloia on sikäli virheellinen, että kanntaindoeuroopan juuri ei ole "**ap-" vaan "*ekʷe-". Gootin sana ahwa osoittaa, että se on laina nimenomaan vasarakirves-kielestä eikä esimerkiksi preussista tai liettuasta tai latviasta, tai tulee suoraan kanta-IE:stä.

|

Joissakin kielissä *h₂ekʷeh₂ menee muotoon:

h₂ep- = water Skr. अप् (apha), Pers. apiyā/āb, Lith úpe; (kuuri: apia, jotv. apis, preussi: appi > sm. Apia, apaja, Ypäjä jne.) *h₂p-isk- "fish" Lat. piscis, Ir. íasc/iasc, Goth. fisks, ON fiskr, Eng. fisc/fish, Gm. fisc / Fisch, Russ. пескарь (peskar'), Polish piskorz Englannin ”f-ish” on siis f- = joki ja -ish adjektiivin pääte: ”jokiolio”!) " http://etimologija.baltnexus.lt/?w=up%C4%97 Alkuperäinen iranilaisten kielten kanssa yhteinen vesi-sana on jokea ja kalavettä tarkoittava upė (lt), upe (lv), apis (jt), appi (pr), apia (kr). Lithuanian: ùpė = joki, apaja Etymology: (-ės), ũpė, žem. upìs (Gen. ùpies), ùpis (-pio, vgl. už úpio bei Daukša; Sereiskis, Šlapelis LLKŽ) 'Strom, Fluss = virta' (upys?, s.v. upis) und 'grosse Menge = suuri määrä, Masse = massa, Strom = virta', Lett. upe 'Fluss, Bach', Demin. upele, upis dass., Lit. ùpė, lett. upe weichen im Vokalismus ebenso Preuss. apus 'Brunnen = kaivo', nicht verkürztes Demin. *apuzē, da dann der Sinn 'Flüsschen = pieni virta' wäre, sondern eine Bildung wie preuss. salus 'Regenbach = sadepuro' Voc. 63: lit. sálti usw. Endzelin, Loewenthal stellen lit. ùpė, lett. upe nach Fortunatovs Vorgang zu preuss. wupyan 'Wolke = aalto' Voc. 9 unter Hinweis auf semasiologische Parallelen (anders Būga KS 296 = Raštai 2, 321, der die Wörter mit lit. ūpas 'Echo = kaiku' usw. verbindet). Interessant ist jedenfalls, dass Pokorny Mél. Pedersen auch Illyrisch und Keltisch in Flussn. die Doubletten up- und ap- aufweisen.

Itägootin vesi-sana on ahʷa, ilmeisestin LÄNSIgootin satama-sana on habna. ... harbor – *habna (f. O) Saamessa on sanasta p-muoto, suomessa sekä k- (Akaa, ahven, Ahri ("Ahti"), Ahvenanmaa että p-muotoja: apaja, Apia ja jopa j-muotoja: aaja = Laaja avoin tasainen suo (SSA).

https://hameemmias.vuodatus.net/lue/2020/11/on-germanic-saami-contacts-and-saami-prehistory " ... In North-western Saami (henceforth NwS), which predecessors of Skolt and Kola Saami,the foreign consonants /h/ and /f/ becameestablished at quite an early date.6 HM: Which are false. A.A.: " Foreign *h-, too, shows a dual treatment: in NwSit was inconsistently either dropped or retained, but in Skolt and Kola Saamialways dropped. Medial *-h- was varyingly either replaced with -k- or -f- or assimilated to a preceding sonorant. Also some initial consonant clusters, especially sk-, were retained in Proto-Scandinavian loanwords in NwS, but simplified in the predecessor of the more eastern Saami idioms. A further consonantalcriterion is that loanwords in the Proto-Scandinavian period frequently show the (hitherto unexplained) sound substitution PScand *-j- > Saami *-č-, which isnot attested in earlier borrowings. The following examples serve to illustrate the phonological characteristics of Proto-Scandinavian loanwords in comparison to the two earlier strata: SaaN áhpi ‘high sea, open sea’ < PS *āpē < PScand *haba- (> Old Norse haf ‘sea’)" HM: Tuo *haba ei ole kantagermaania vaan ehkä länsigoottia. |

" ... The strong verbs of modern standard German may also leave traces of prehistoric language contact induced change. In his examination of Germanic strong verbs, Robert Mailhammer concluded that “46.5% of all Germanic strong verbs do not have an accepted Indo-European etymology” (2007: 167-187). Mailhammer suggests (2007: 175) that convergence of a non-Indo-European language with Proto-Indo-Euro-pean may explain the identifying feature that strong verb ablaut is for the Germanic languages. Moreover, Mailhammer (2007:199) suggests that language contact between speakers of Punic (a Semitic language spoken by the Carthaginians) and Germanic may explain the unique role played by ablaut in Germanic strong verbs. He asserts that the systemization and function of ablaut found in Germanic strong verbs are typologically more similar to that found in Semitic languages than that in Indo-European languages. His views prompt arguments for further research in Germanic languages from the perspective of language contact theory.

2.4 Germanic Origins from the Perspective of Archaeology.

In English, the word “Germanic”sounds very similar to the word “Ger-man. ”Modern German, however, makes a distinction using the terms der Germane and der Deutsche. Thus, reader should not confuse the terms Germanic tribe sor peoples with modern-day Germans for both terms are ethnically distinct. In my opinion, a convenient starting point for the emergence of the Germans as an ethnic group is the ninth century and the division of Charlemagne´s kingdom among his grandsons.

The Germanic tribes, on the other hand, appeared in the historical re-cord around 113 BC near the current Austrian/Italian border,where the Cimbri and Teutones, two Germanic tribes, fought a battle against the Romans.

[HM: They were not Germans: they had no Grimm´s law changes in their language.]

According to Seyer (1988: 37), the Romans did not initially distinguish the Germanic tribes from the Celts. Rather,the Romans made this dis-tinction about 50 years later. According to Seyer (41), the word Ger-manic first appeared in the work of the Roman historian Poseido-nious to describe the “border neighbors of the Celts on the right bank of the Rhine.” After making their grand entrance onto the historical re-cord, the Germanic tribes fought largely amongst themselves, and of-ten with the Romans, for territory and plunder.The story of the Germa- nic tribes eventually ended with the Saxon Wars at the end of the eighth century, when Charlemagne defeated a Saxon uprising led by Widukind.

Stepping away from recorded history, this dissertation now explores if the Germanic tribes had a prehistory.Since this covers a period before recorded history,the traditional approach to answering such a question is archaeology and the artifacts left behind by prehistoric people. Interestingly food waste, known as kitchen middens, may present the archaeological starting point for researching the prehistoric Germanic peoples. The kitchen middens in Denmark were left behind by the Me-solithic Ertebølle culture. By 5400 BC,the Ertebølle culture had alrea- dy constructed permanent settlements along the coastline of northern Germany, Denmark and southern Scandinavia (e.g. Hartz 2007:573). The construction of permanent settlements represents atypical Meso-lithic behavior,providing evidence that the Mesolithic inhabitants of the Germanic homeland had indeed found a unique survival strategy by exploiting locally available marine resources. Hunter-gatherer cultures generally do not build permanent settlements, but rather this cultural behavior is Neolithic and associated with the rise of agriculture. My re-search in Demark revealed that mussels are one factor in understan-ding how the Ertebølle culturefound a unique survival strategy. The kitchen waste left by this culture consists mostly of mussel shells. The Ertebølle culture had access to an abundant supply of mussels, which are highly nutritious. Even today along the shore of the Limfjord,a fjord adjacent to some of the Ertebølle settlements, an abundance of mus-sels is still found. An abundant supply of locally supplied marine re-sources meant that the Ertebølle culture could remain in one location. The same food source may have also increased fertility and had corresponding effect on population density.

In 1849, Danish scientists established a commission to examine the kitchen middens left behind by the prehistoric inhabitants of Denmark. Kristian Kristiansen (2002:21-22) defines this commission as the beginning of modern archaeology in Denmark. Perhaps even more significant, Kristiansen (12-13) asserts that archaeology in Denmark was the beginning of archaeology as an international and independent discipline.

Danish archaeology, in turn, influenced the work of Gustaf Kossinna (1858 - 1931), the father of German anthropology. In his 1896 article, “Die vorgeschichtliche Ausbreitung der Germanen in Deutschland,” Kossinna (1) cited the work of Jens Jacob Asmussen Worsaae (1821 - 1885), one of the founders of Danish archaeology and a key player in the kitchen middens commission. Kossinna (1) used Wor-saae´s research, along with his own research, and that of the other ar-chaeologists of his time,to dispute linguistic interpretations that placed the homeland of Germanic peoples in Asia. Rather than Asia, Kossin-na (14) identified Northern Germany, Denmark and southern Sweden as the homeland of Germanic peoples.

Since Kossinna made his proposal, linguists (e.g. Nielsen 1989: 39) have consistently identified this area of Europe as the homeland of the Germanic peoples and the geographic point of origin for Germanic languages. 2.5The “Kossinna Syndrome.”Prior to the Second World War, the prehistory of the Germanic peoples represented a potential research direction among scholars. However, since the war this re-search direction has become taboo, especially among German acade-mics. The avoidance of Germanic prehistory is sometimes labeled the “Kossinna Syndrome.” Nevertheless, it appears that some German academics believe that it is time for a change.

In 2000, Sabine Wolfram, a German archaeologist, published an ar-ticle maintaining that the “Kossinna Syndrome,” has hindered German archaeology,and that German archaeologists have a severe handicap- compared to their British and American counterparts. Using the term Vorsprung durch Technik, meaning „progress through technical detail,‟ she (184) criticizes the lack of theoretical debate in German archaeo-logy,that German archeology is mostly focused on empirical and data-oriented approaches, and avoids building models.

A German-American archaeologist, Bettina Arnold, offered a similar critic of German archaeology. She ( 2000:401) wrote “there is no theoretical foundation [in German archaeology] apart from the need to distance all archaeological research from theory". In my opinion, Wolfram´s and Arnold´s criticism is meant to address how German archaeology is essentially devoid of any ethnographic assessment of archaeological remains.

Wolfram attributes the avoidance of theoretical debate to a failure of German archaeology to openly discuss the “ideological misuse of archaeology during the Third Reich.” According to Wolfram (184-185), rather than discussing this issue, German archaeologists have turned Gustaf Kossinna into a scapegoat. For example, Karl Heinz Otto (1988:29), a German archaeologist in the former East Germany, writes: The result of Kossinna‟s archeological-historical approach to archaeological theory was extraordinarily tragic. His archaeological theory, tainted by his nationalistic, ethno-centric, and racist views, led to the use of Germanic prehistory as support for imperialism and ultimately a fascist ideology ...

Kossinna's archaeological work asserted an undisturbed development of Germanic ethnicity since the Mesolithic, where Southern Scandina-via, Denmark and Schleswig-Holstein are seen as “purely Germanic soil” since the Late Neolithic. 1

Commenting on Kossinna‟s theoretical approach to archaeology, Bet-tina Arnold (1990: 464), writes: The groundwork for an ethnocentric German prehistory was laid by Gustaf Kossinna ... [who] proposed cultural diffusion as a process whereby influences, ideas and models were passed on by more advanced peoples to the less advanced with which they came in contact. This concept, wedded to Kossinna´s Kul-turkreistheory, the identification of geographical regions with specific ethnic groups on the basis of material culture, lent theoretical support to the expansionistic policies of Nazi Germany.

Heinz Grunert (2002: 339), Kossinna´s biographer, writes: His ... monographs, above all the German Prehistory - an Essential National Science and the several versions of work published under the title Old-Germanic Cultural Greatness... were objectively suitable to white-wash a national socialist ideology (or for what passed as an ideology) lacking in substance with a coat of scientific authority. Kossinna appa-rently submitted proof of an alleged German historical right to expand into other middle and eastern European territories. He contributed to fusing ethnic and national identity with race. In the process he strengthened the maxim of alleged racial superiority and the cultural supremacy of Germans over other cultures. In doing so he delivered important arguments for the justification and legitimatization of Nazi politicians, who were demagogic, ethnocentric and finally genocidal. The term “Kossinna Syndrome” actually comes froman article pub-lished by Günter Smolla, a German archaeologist, in 1979/80. Smolla used this term to object to those who attacked Kossinna, both perso-nally and professionally, in the post-war era. Smolla (1979/80: 8) takes the position that Kossinna was a “normal scholar.”

1 All translations from German are mine.

He writes: Kossinna remains a significant yet rather difficult scholar, retaining both positive and negative character traits. His work shows both factual and methodological mistakes, but also correct and even stimulating findings. Apparently he was a „normal‟ scholar. As soon as he recognized that he could proceed with the archaeological record where the linguistic evidence had hit a dead-end, he passionately attempted to present a dynamic picture of prehistory using ethnic groups whose identity were partially gleaned from areas that they had apparently occupied or vacated. The fact that he used terminology such as Germanic peoples or Indo-Europeans reflects a tradition that he encountered during his university education. He was essentially a product of his generation, adapting his theories to existing preconceptions, not one who re-invented the wheel.

My exhaustive review of Kossinna´s life and work has failed to find any evidence of sympathy or association with the Nazi Party. More-over, he died in 1932 before the Nazi Party came to power. On the contrary, after spending countless hours trying to uncover the great sin of German archaeology, I conclude that Kossinna has indeed become a convenient scapegoat.

In my opinion, an honest assessment of the disgraceful direction that German archaeology took between 1933 and 1945 would fail to find fault with Kossinna, but rather would fault a Nazi organization called Ahnenerbe. The word Ahnenerbe is difficult to translate into English. Some (e.g. McCann 1994: 79) translate the term as “ancestral inheri-tance.” In my opinion, “German heritage” would be a better translation. I will simply use the German word for this organization.

Ahnenerbe was created in 1934 by Heinrich Himmler,a leading figure in the Nazi regime. In Nazi Germany, Ahnenerbe allocated almost all of the funding for archaeological projects investigating the prehistory of Germanic peoples.

These projects were funded to promote a belief in German racial superiority. Some of these projects were simply bizarre. For example, Ahnenerbe investigated a rumor that the ancient Germans procreated during the mid-summer so children could be born in the following Spring. The goal of the inquiry was to develop guidelines for the Ger-man soldiers in their duty to produce racially pure offspring (Pringle 2006: 121).

Another bizarre research project involved “world ice theory,” that an ancient catastrophe had blanked the entire world with ice except for a few remote areas at high altitude.An expedition to Bolivia was planned to determine if ancient Germans in the New World survived the catastrophe (Pringle 2006: 178-180).

After the start of the Second World War, military projects took center stage in Ahnenerbe research. At this point,Ahnenerbe research turned from bizarre to inhuman. Dr.Sigmund Rascher, an Ahnenerberesear-cher, conducted ghastly medical experiments on prisoners at the Dachau concentration camp (Kater 1974: 231 - 245).

Another project, led by Dr. August Hirt,also an Ahnenerberesearcher, assembled a collection of skeletons using the corpses of prisoners that were gassed at the Natzweiler-Struthof concentration camp (Kater 1974: 245-255).

Clearly, the controversy surrounding Gustav Kossinna and the emer-gence of Ahnenerbe have tainted the search for Germanic origins. Scholars who explore Germanic origins must recognize that this research direction has the potential for abuse among those agenda is ethnocentric.

In my opinion, an ethical and scholarly approach to exploring Germa-nic origins first views this language group as simply a co-equal member of the global linguistic tapestry.

Secondly, the goal of this inquiry should merely attempt to better understand global language variation.

2.6 Germanic Origins from the Perspective of the Y-Chromosome.

The goal of this dissertation is to demonstrate that genetic data, espe-cially Y-chromosome data, are a useful tool for evaluating models of Germanic origins.

My research has uncovered a single published report that used Y- chromosome data for exploring Germanic origins. The paper was pub-lished in 2008 by Kalevi Wiik, a phonetician and professor emeritus at the University of Turku in Finland. He posits (83) that emergence of Proto-Germanic involved language shift from Uralic to Germanic. Nevertheless, in my opinion the potential of population genetics still remains a research direction that has not been fully appreciated by some researchers. Perhaps one explanation is that this research has only emerged in the last decade.Geneticists began to focus on human molecular variation about thirty years ago. However, the pace of this inquiry finally accelerated in the late 1990s with the development of new technology such as Denaturing - High Performance Liquid Chro-matography (D-HPLC), a development that has made the detection of Y-Chromosome mutations “easy, fast and inexpensive” (Francalacci and Sanna 2008:60). This development triggered a flood of population reports, beginning in 2000, describing world-wide Y-haplogroup varia-tion and the evolutionary history of various human populations. During my research, I found that Y-chromosome data are currently very frag-mented, which may also explain why this research direction remains unrecognized by some in the academic community. For this disserta-tion I actually had to gather my data from approximately two hundred and forty published reports.

Another huge problem for the some researchers is the nomenclature system used by geneticists to describe Y-chromosome variation. This system has been at times inconsistent, and subject to refinement and revision. Initially, geneticists used several different nomenclature systems to describe Y-chromosome haplogroups.

For example, Rosser (2000) used “Haplogroup 3” to describe the cur-rent R-M17 mutation, whereas Semino (2000a) used “Eu 19.” In 2002 the Y-chromosome Commission standardized the nomenclature and “R1a1” became the cladistic label for the R-M17 mutation.In 2008, Ka- rafet and others revised the nomenclature system and, for example, the cladistic description for the M178 mutation changed from “N3a” to “N1c1.” In addition to the two official revisions I just described, a num-ber of “unofficial” revisions have also taken place,where a group of researchers rather than a specific organization change the nomencla-ture. Moreover, researches sometimes use a nomenclature that is dif-ferent from the official standard, or different from that used by another researcher. Please refer to the table below.

As shown in Table 2.3, Rootsi and others defined four common sub-clades of the I-M170 mutation in 2004. In 2007, Underhill and others revised the classification. However, Karafet did not recognize the new I-M423 mutation,and used the old I-P37.2 mutation. For the I-M26 mu- tation, Karafet also used a different cladistic description, “I2a2” rather than“I2a1.” Battaglia,in 2009,used the I-M423 mutation from Underhill, but with a different cladistic description. The same report adopted Ka-rafet‟s cladistic description for the I-M26 mutation.In 2009,Mirabel and others continued to use the I-P37.2 mutation rather than the Underhill I-M423 mutation, but nevertheless used the Underhill cladistic descrip-tion for the I-M26 mutation, rather than the one used by Karafet and Battaglia. In the 2009 report by Pala and others,the researchers adopt the same nomenclature as Battaglia.

A final reason why Y-chromosome data may be underutilized is that the target audience for published research in this area has been large-ly geneticists. In my opinion, the methodology of population genetics needs to be explicated so that a wider audience can evaluate the potential of this new research. This task will be undertaken in the next chapter.

2.7 Chapter Conclusion.

This chapter defines Germanic as a branch of the Indo-European lan-guage family. As such, the origins of Germanic languages are linked to the origins of Indo-European languages. Today, the linguist encoun-ters two different models attempting to explain the putative homeland and the expansion of Indo-European languages across Europe, either the diffusion of agricultural technology across Europe, or alternatively the Kurgan expansion.

Traditionally, two different linguistic approaches have been used to explain why Germanic is a part of the Indo-European language family, Stammbaum Theory and Language Contact Theory. Either Germanic diverged from Proto-Indo-European and developed independently, or alternatively, two or more languages converged to produce Germanic.

The archaeological approach to Germanic origins posits southern Sweden, Denmark and northern Germany as the putative Germanic homeland.

Unfortunately, archaeological research into the prehistory of Germanic peoples has stagnated since 1945 and the end of the Second World War. Finally, this chapter introduces a potential new tool for exploring the origins of Germanic languages. However, this research remains underutilized due to the fragmented reporting of the data,and inconsis- tent nomenclature system, and a methodology that awaits further clarification.

Chapter Three

Why the Y?

The Y-Chromosomeas a Tool for Understanding Prehistoric Migration.

3.0 Chapter Introduction.

In this chapter I will explain how Y-chromosome data has emerged as a powerful tool for tracing prehistoric migration and settlement. By avoiding recombination, the Y chromosome provides a genetic record that is transmitted largely intact from one generation to the next. Ne-vertheless, single nucleotide polymorphisms, a type of genetic muta-tion,distinguishone Y-chromosome from the next.The term haplogroup is used to refer to these mutations. Moreover, short tandem repeats, another type of mutation,provides a means of dating the evolution of a haplogroup. By examining haplogroup frequencies in modern popula-tions,and by having a rough idea when the various haplogroups arose, geneticists are able to postulate several population expansions that define the human prehistory. While the Y-chromosome represents one of several potential sources of genetic data for deciphering prehistoric human population expansion, this dissertation focuses on Y-chromo-some data because of the volume of published data, and because this data is easier to understand.

3.1 Playing by-the-Rules.

In their article “The human Y chromosome: an evolutionary marker comes of age", Mark A. Jobling and Chris Tyler-Smith, two geneti-cists, claim that the Y-chromosome does not play according to the rules of genetics, and for this reason has emerged as “a superb tool for investigating recent human evolution from a male perspective” (2003: 598).

In order to understand how the Y-chromosome behaves differently from other human chromosomes, at least from the viewpoint of geneti-cists, it is necessary to briefly discuss Mendelian genetics, which is often part of high school and introductory college biology instruction. According to Mendelian genetics, we inherit our genes from both parents. However, the Y-chromosome plays by its own genetic rules in that it is only passed from a man to his son.The Y-chromosome is one of the two sex-chromosomes in the human genetic inventory,or human genome. The other sex chromosome is the X-chromosome.During human reproduction, two X-chromosomes yield female offspring, and an X-chromosome and a Y-chromosome yield male offspring.

Consequently, a male can only inherit the Y-chromosome from his father. Another “rule” of Mendelian genetics is recombination. During human reproduction, the genetic cards are essentially “reshuffled", or more precisely, recombination occurs. For example, Mendelian gene-tics would define hair color as a genetic trait or phenotype, and varia-tions of this phenotype, such as blonde hair and red hair, as alleles. Because of recombination, parents may have blonde hair, but their child itself may potentially inherit red hair from a grandparent.

However, the genetic material contained in the Y-chromosome, for the most part, escapes recombination, providing yet another example of failing to follow the rules of genetics.In order to explain how the Y-chromosome avoids recombination, it is necessary to briefly discuss the evolutionary history of this chromosome. The sex-determining locus of the Y-chromosome not only codes for maleness in humans, but in all mammals. This section of the Y-chromosome, however, only represents a fraction of its entire length.During the evolutionary history of mammals, about 300 million years, the Y-chromosome has, in the words of some geneticists, slowly “degenerated” or degraded (Lahn et al. 2001: 211). When mammals first evolved, the Y-chromosome “behaved normally” in that theentire chromosome recombined with the X-chromosome. Now, as the result of slowly evolving structural decay, about 95% of the entire length of the Y-chromosome has been damaged, emerging in what the geneticists call a “non-recombining region.” This largenon-recombining region means that during human reproduction, very little genetic exchange occurs between the X and Y chromosome. Consequently, the Y-chromosome is transmitted from one male to the next largely intact.

3.2 Mutation.

So far this chapter has explained that the Y-chromosome is unique, partly due to uni-parental inheritance, and partly due to the absence of recombination. Consequently,men inherit a large section of genetic in-formation that remains unalteredfrom their fathers. However, the non-recombining region of the Y-chromosome can and often varies from one Y-chromosome to the next. Geneticists describe this variation as mutation. In population studies examining Y-chromosome variation, two different types of mutation are particularly informative: single nucleotide polymorphisms and short tandem repeats.

Before discussing Y-chromosome mutations in detail,I want to empha- size a concept known as neutral selection. I emphasize this concept to avoid misconceptions that may arise among those whose knowledge of human genetics is rudimentary.Those who have taken an introduc-tory biology or physical anthropology course have probably encounte-red the term “natural selection,” initially proposed by the naturalist Charles Darwin. This theory accounts for different animal and plant species based on fitness, or survival of the fittest. According to this theory, differentiation among species arose as the result of a mutation that enabled the plant or animal to survive in a given environment long enough to pass on its genes to the next generation. Y-chromosome mutations, however, are classified as selectively neutral, meaning they do not confer any reproductive advantage.

Another point also needs to be clarified before discussing Y-chromo-some mutations. As explained earlier, Y-chromosome mutations are not reproductively advantageous. Likewise, these mutations are not disadvantageous. Introductory biology courses often emphasize that genetic mutations can be harmful or fatal to living organisms. For example, among humans one of the most recognized harmful genetic mutations is sickle cell anemia. In contrast to sickle cell anemia and other genetic mutations, Y-chromosome mutations are totally benign. This explains, partially, why Y-chromosome mutations survive, while many genetic mutations affect reproductive success and are consequently eliminated from the gene pool.

3.2.1 Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms.

As detailed above, the non-combining region of the Y-chromosome can vary from one male to the next because of mutations which are selectively neutral and benign. Furthermore, two different types of mu-tations have emerged as particularly informative in examining popula-tion history from a male perspective. One of these mutations is classi-fied as a single nucleotide polymorphism. This mutation is also descri-bed in population reports as a unique mutational event, or as a haplo-group, or as a clade, and sometimes as an allele. For the non-geneti-cist, the use of so many essentially synonymous terms certainly poses a challenge in understanding the literature.

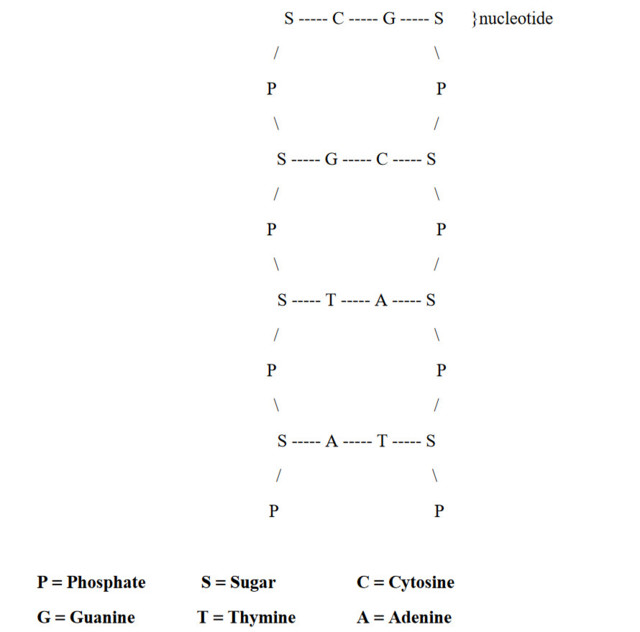

Focusing now on the term single nucleotide polymorphism, it is useful to discuss the structure of DNA, short for deoxyribonucleic acid (cf. Figure 3.1 below). The structure of DNA resembles that of the non-recombining region of the Y-chromosome. This molecular “ladder” has “rails” formed by alternating sugar and phosphate molecules The “rungs” of this ladder, known as nucleotides, are formed by bonding two molecules having a nitrogenous base;either adenine and thymine, or guanine and cytosine. The order of the bonding can alternate, mea-ning the nucleotides appear in one of four different combinations: ade-nine-thymine, thymine-adenine, guanine-cytosine and cytosine-gua-nine. A single nucleotide polymorphism occurs when one of the rungs of our molecular ladder changes,or mutates.An example of a mutation would be a nucleotide reversal from adenine-thymine to thymine-ade-nine.Sometimes a mutation entails the addition or deletionof a nucleo- tide. These single nucleotide polymorphisms are sometimes referred to in population reports as unique mutational events, because they are so rare they only occur once during human evolution.The evolutionary rate of mutation for single nucleotide polymorphisms is estimated to be about 10-8 per base pair per generation (Novelletto 2007: 140). Since the non-recombining section of the Y-chromosome has about 60 million molecular “rungs,” or base pairs, geneticists have a vast region of genetic information to harvest the evolutionary history of human males.

As explained in the above paragraph,single nucleotide polymorphisms are a common mutation occurring in the non-combining region of the Y-chromosome. Geneticists comb the non-recombining region to iden-tify these mutations. The presence or absence of these mutations, or single nucleotidepolymorphisms, can distinguish the Y-chromosomes of one male population from the next.Another and perhaps more com- mon label for a single nucleotidepolymorphism is the term haplogroup. Haplogroups are reported in population reports using a nomenclature system first standardized in 2002 by the Y Chromosome Consortium. This standard uses an uppercase letter to identify major haplogroups. An uppercase letter followed by a combination of numbers and lower case letters is used to report sub-haplogroups.

Figure 3.1 The Structure of DNA.The fact that nucleotide bases vary is central to population genetics.

Haplogroup nomenclature often adds the mutation number, usually prefixed with the abbreviation “M,” and sometimes “P” or “V.” For example,one very common haplogroup found in Europe is I-M170, the “I” meaning haplogroup I, the M170 referring to mutation number 170. An example of a sub-haplogroup is the I1-M253 mutation, commonly found in Scandinavia.The “1” is used to classify I1-M253 as a sub-hap- logroup of haplogroup I. Often the literature does not make a formal distinction between major haplogroups and sub-haplogroups, and thus I-M170 and I1-M253 would simply be reported as “haplo-groups.”

Haplogroups and their subgroups represent terminology used to build phylogenetic trees, hierarchical relationships between polymorphisms, very much akin to language trees utilized by linguists. Since the methodology used to build these hierarchicalrelationships is called cladistics,the terms clade and subclade are sometime used to label haplogroups and sub-haplogroups.

3.2.2 Short Tandem Repeats.